Associate Professor of Biology Nicholas Gidmark keeps a roadkill collection kit in his trunk at all times. He carries gloves, bags, zip ties, and anything else he needs for corpse collection. Where others may be sad or disgusted when they see a dead animal on the side of the road, for Gidmark it’s an opportunity.

“We had an armadillo that was actually collected by me during a family vacation road trip,” Gidmark said. “I had to strap it to the roof because it smelled too bad in the trunk.”

The specimens, as he calls them, are for Biology 325 Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy. The class has two lab periods a week, compared to most lab classes which only have one. The labs are almost all dissections.

They dissect lampreys, sharks, bony fish, frogs, salamanders, birds, rabbits, even cats and stillborn bison – basically anything Gidmark can get his hands on.

Near the end of the term, students are given a bucket of bones and told to turn them into a fully articulated skeleton – an infamously difficult project in the biology department.

“So first of all, I don’t hunt them. I don’t kill anything,” he said.

Many of the fish and sharks come from a marine lab in Maine where Gidmark works in the summer. A dog skeleton on display in the lab was donated by a coworker of Gidmark’s, who wanted her deceased pet used for science.

Some, like a stillborn bison the class dissected this year, come from Wildlife Prairie Park. Gidmark’s class has dissected and articulated elk and bison which died of natural causes at the park.

Others still, come from the mysterious web of guys who know guys that Gidmark has curated. Despite the haphazard collection of specimens, Gidmark says they never have a shortage.

Fresh specimens are kept frozen. The class dissects them and removes the flesh before putting them through a process of accelerated rotting. The bones are then disinfected with ammonia and degreasing chemicals so they can be handled safely. Once the bones are processed, they have a very long shelf life and can be saved for whenever the class needs them.

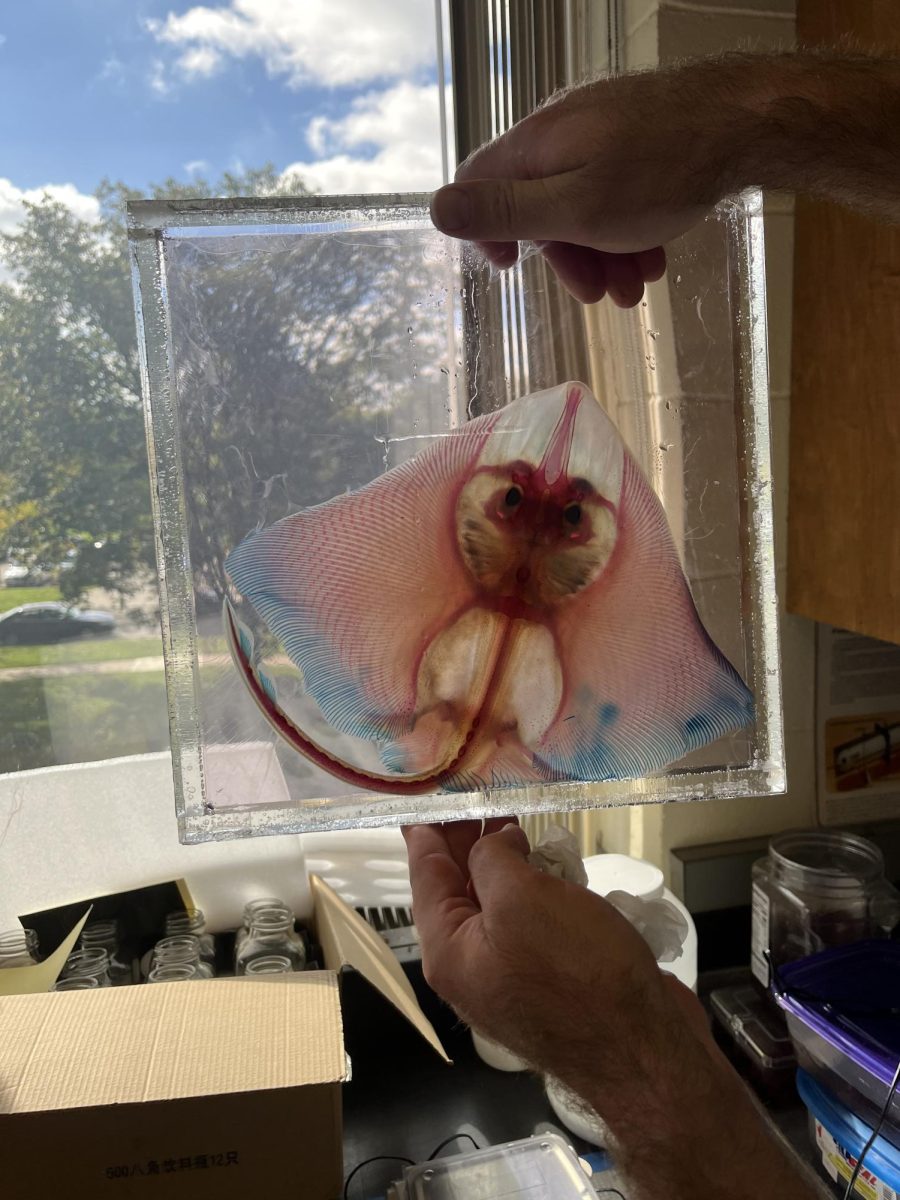

Sharks and other cartilaginous fishes often go through a different process – diaphonization, which essentially turns the soft tissues clear, leaving the bones blue and cartilage red.

Each student in Bio 325 goes home with some sort of fish they processed themselves, though it takes the whole quarter. Gidmark and the teaching assistants perform the process with the students, preparing specimens for study.

“We can pull them apart, we can look at what species are, what different bones are shaped like across different species,” he said.

The goal of all this dissection and articulation, he says, is for students to physically get into an animal and see how they’re connected.

“Sorting these things, especially things like those vertebrae, requires you to really figure out how do these go together and what’s going to change along the length of the skeleton,” he said. “Because it turns out that vertebrae from the neck are going to do very different things from the vertebrae in your torso versus vertebrae in your tail.”

Most of the students who take this class are Biology majors, especially pre-health students. But they’re not the only ones interested in how bodies are connected.

“We get a lot of athletes actually, who are just interested in bodies, in motion,” Gidmark said. “Which I think is a really fun kind of cross campus interaction.”

Every lab in the class is designed to help students gain a deeper understanding of what different animals are shaped like, and why that might be.

“It’s like, let’s just explore. Let’s just check some stuff out and see what happens,” he said.

Winner 1st Place Features Illinois College Press Association 2024

Hannah • Nov 13, 2023 at 2:11 pm

Fascinating! I love to hear about what happens in classes that I don’t necessarily want to take. But it’s so cool to see what others are doing!