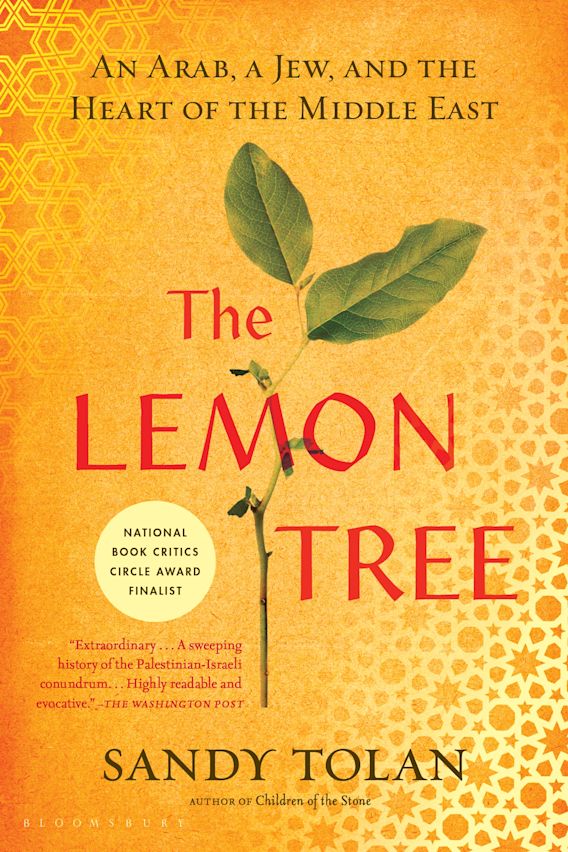

When I enrolled in Intro to Middle Eastern Politics this fall, I was expecting to hear a westernized curriculum explaining genocide gingerly using political terms and technicalities. I was only enrolling to get a graduation requirement out of the way. When we were assigned readings from The Lemon Tree, I was apprehensive to read an American writer’s attempt to reflect both the Palestinian and Israeli perspectives. As I read the book, the “story of the Other,” as the author, Sandy Tolan, calls it, I was shocked.

If you do not understand the conflict and don’t know where to begin then this is the right book for you. If you want to understand Palestinian resilience and the history of Israel from a unique voice that you may previously not have come across, then this is the perfect book to do so. Or if you just want to hear the voice of a people propagating a cycle of violence of which they were once a victim, and a people experiencing that violence, then you must read this book.

The book opens with Bashir’s climactic journey from Ramallah into the “alien” world called Israel where his hometown, al-Ramla, is separated from him, not just by 46 kilometers but decades of occupation and genocide. Before we even realize the significance of this journey within the stories of Bashir Khairi and Dalia Eshkenazi, the Arab and Jewish protagonists, respectively, Tolan introduces Dalia. Two irreconcilable characters finally meet later in the story after Tolan retells the story of Bashir’s family, the Khairi clan, and their expulsion from al-Ramla, and the Eshkenazis’ journey from Bulgaria to the Promised Land of Israel. Soon after the Khairis were expelled, the Eshkenazis arrived with their baby daughter, Dalia, in 1948. On arrival, they were told by the Jewish forces to pick a house of their choice to live in.

“Generally, it can be said that any Arab house that survived the impact of the war… now shelters a Jewish family,” said Tolan.

The house picked by the Eshkenazis later unites Bashir and Dalia. Within the house stood the memorable lemon tree that the Khairi clan had planted together, an eternal symbol of their deep connection to their land, and their home. It was the house that Bashir’s father, Ahmed Khairi, had built for his family. He had laid down the first brick and put “stone upon mortar upon stone,” with “cousins, friends and hired laborers.”

Years later, as Bashir and Dalia meet, the most surprising fact about their meeting is the amiability with which Dalia treats Bashir, as she allows him into her house, or his house, and how Bashir reciprocates the amiability by inviting her to his new home in Ramallah.

As Bashir argues the Arab cause with a Zionist, Dalia is taken aback by his calm demeanor and firm belief in the liberation of the Palestinian people. Later in the story, because of this belief, he finds himself accused of bombing a supermarket in Israel and is profusely tortured in the Israeli prison. The stories of torture and gore are used as embodiments of the violence of the Israeli occupation and the dehumanization of Palestinian bodies. With fury and profound sadness, the reader learns about how Dalia and Bashir maintain their connection, and how she deals with the weight of her stolen house standing on stolen land.

Bashir’s father also visits the house before his death and the feelings of catharsis, helplessness, and hope intermingle at the close of the story as he returns to the tree, and drinks lemonade made from lemons picked for the tree.

“Of course it was nice! We planted that tree with our own hands. Dalia’s family—they were all very kind. But what does it matter? They were the people who took our house,” said Nuha, Bashir’s sister.

The book leaves you with the lingering thought about how to feel about the very nice people who took your house. After all, houses often tell more stories than history books or romance novels, and within bricks lie the truth of the people silenced and shunned by all, the Khairis, the Palestinians.

Raina Lefkowitz • Dec 1, 2024 at 1:22 pm

Just to be clear, Dalia’s family came to Israel for Bulgaria after, and as a result of, the Holocaust. Your reviewer presents them as if they were simply looking for someplace to live, not as ones seeking refuge from the unspeakable horrors they experienced. The point of the book is that Dalia and Bashir share in the tragedy, and try to come to terms with their conflicting understandings. It would be interesting to see their comments now after the Hamas massacre last year.