Exploring the Impact of College Students Voting on American Democracy

Photos by Eleanor Lindenmayer

Are you planning on voting in the midterm elections?

“Yes,”

“Maybe,”

“When is that again?,”

“Absolutely,”

“No,”

“Of course,”

“Oh yeah that is coming up, isn’t it?”

“What is that?”

These are just some of the responses to a lunchtime poll performed by The Knox Student (TKS). 79 students were surveyed outside The Hard Knox Café, and asked that one simple question, “Are you planning on voting?”. If the answer was no, there was a follow up: “Why?”

“I don’t know how,”

“I’m not sure if I should vote here or at home,”

“I don’t know how to get an absentee ballot,”

“I’m not a US citizen,”

“I forgot to request my ballot,”

Knox College currently enrolls 1,053 students, and excluding the approximately 200 international students, that leaves 853 who are able to vote – sans a few first-years that may not be 18 yet.

So, are they voting? And are other students around the country? And most importantly, why does this matter?

Are Students Voting?

If the results of this survey are unbiased and representative – unlikely, as it was not taken by trained pollsters – 63.3% of Knox students are planning on voting in the upcoming midterm elections. Though, the question of whether those who declined to answer the lunchtime poll (of which there were far more of than responders) are the same or a similar group to those who are not planning on voting, is important to consider.

According to the National Study of Learning, Voting, and Engagement 66% of registered college students voted in 2020 – 14% more than the number of students who voted in 2016.

This statistic is slightly misleading. It only represents the percentage of registered students who voted. To know what percentage of students voted, they’d need to count unregistered students as well. So it can be assumed that the number of college students voting is below, perhaps significantly below 66%.

This puts the Knox College numbers above the average.

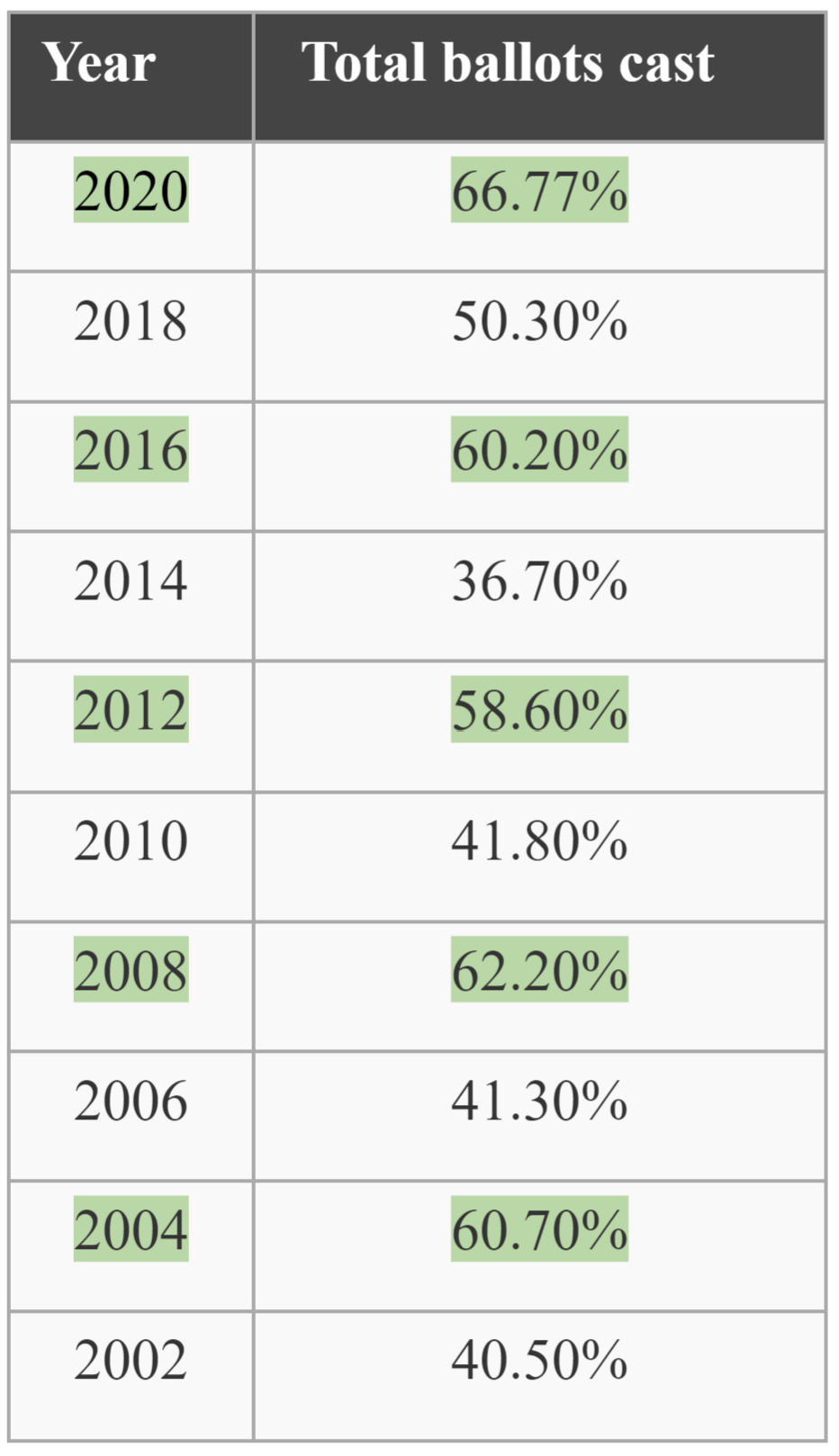

Below is a table created by Ballotpedia showing total voter turnout of all eligible voters over the past twenty years with presidential election years highlighted in green.

Voter turnout fluctuates but increases and decreases pretty reliably depending on whether it is a presidential or midterm election, coming in around 60% normally for presidential contests. If college students voted at the same rates as older adults, their turnout would be expected to be 60% as well, but it’s not.

A National Election Commissions and Research Agencies study showed that fewer than half of Americans ages 18 to 29 voted in 2016. Another study by Daniela F. Melo of the Department Of Political Science at University of Connecticut and Daniel Stockemer of the School of Political Science at University of Ottawa found similar results, indicating that, “younger generations are less likely to vote than their older counterparts,”. Baker Center at Georgetown University found that 58% of all eligible college students voted in 2016, lower than the American average.

College students are voting at lower levels than older adults, there is no consensus on by what proportion, but it is happening.

Why?

Charlotte Hill from the University of California, Berkeley, suggests that voter suppression may play a role. Voter suppression always impacts those who are less likely to vote more than those who are more likely, including young people, minorities, less educated people, and people of a lower-socioeconomic status.

But Knox Associate Professor of Political Science and Chair of Public Policy Andrew Civettini doesn’t believe that to be the main issue.

“The academic research on [voter suppression] says that [it] doesn’t matter,” Civettini said. “They don’t change who participates, and to the extent that they do, they actually decrease it for both parties.”

Basically, those who are going to vote, will, and voter suppression measures won’t stop them. So, what is stopping college students?

The answer appears to be simple – something called opportunity cost.

“Just like economics, it’s a simple thing,” Civettini said. “When you increase the cost for something, the demand goes down.”

Those costs can be many things: less flexible schedules, inability to take time off, lack of community ties, differing voting registration rules state to state. It’s a common misconception that if it is a federal election the federal government runs it – but that’s not the case. In almost every state a person must register, which adds an additional step before voting. Sometimes this process is complicated. Out of state students need to travel home or request an absentee ballot, which adds another step before voting.

“When you make voting harder by increasing the artificial cost of it, even if it’s nominal. ‘Oh, I have to travel five minutes instead of two minutes to get to my polling place,’ somebody is going to use that as a reason not to participate,” Civettini said.

The exposure a student has to voting and political education before college has a large impact on whether or not students will vote once eligible.

“Ultimately, the best predictor about whether or not young people will participate in elections is whether or not their parents did,” Civettini said. “The single biggest predictor of who you’re going to vote for is who your parents vote for.”

Both parental guidance and civics education can be very important. Every state requires some coursework in civics or social studies in order to graduate, but these requirements vary dramatically across the country. And often, according to Civettini, civics is the most neglected department in secondary education. Amending this problem is one of the many solutions posited to increase student voter turnout.

Solutions

Professor of government at American University Jan Leighley suggests teaching how to register, how a ballot works, how to go to the polls, and anything else students need to know about how to vote in their state, in high school civics class. In some states students can even pre register in class with a civics teacher available to support them through the process. According to University of Chicago Professor Anthony Fowler, this preregistration can increase turnout by 2.1 percentage points.

Another option is automatic registration when interacting with another government agency – like getting a driver’s license or passport. Twenty-one states including D.C. currently have automatic registration policies.

But if students make it to college without being registered, colleges can also do a lot to help. Tufts University even argues that, “Preparing college and university students for responsible stewardship of a robust democracy has long been the core mission of American higher education,”.

A study by Professor of Political Science at Indiana University South Bend Elizabeth A. Bennion and Associate Professor of Political Science at Temple University David W. Nickerson, found that emailing students a downloadable voter registration form increased registration rates by 0.6 percentage points, but did not affect turnout. But when students were emailed the link to an online registration, portal registration increased by 1.2 percentage points, and turnout increased by 0.5 percentage points, which is statistically significant.

Several studies examined the impact of students or professors giving voting registration presentations in classes. Another study by Bennion and Nickerson found that, “Presentations by both students and professors increased voter registration rates by approximately 6 percentage points. Voter turnout rates increased by 2.6 percentage points,”.

A study published in the journal Political Behavior focused more on voter engagement,finding that discussions about voting with peers increased the likelihood that those already registered would vote, but did not seem to impact how many students were registered.

Civettini says that getting students to that first election is the most important part, because, “the biggest predictor for whether or not you vote in your second election is whether or not you voted in your first election,”.

Voting is habitual: the more you do it, the more likely you are to do it again, especially if those around you are doing it as well.

Though voter suppression is not a large part of why college students don’t vote, decreasing voter suppression will increase voter participation for all groups, including college students.

“The conventional wisdom is when you make elections easier to participate in, more people participate – that’s true,” Civettini said. “The conventional wisdom is also when more people participate, democrats do better, and the evidence for that is actually pretty mixed. For the most part research shows that few election outcomes would change if you took turnout from sixty percent to eighty percent.”

Importance and Impact of College Voters

Civettini is right – statistically, one vote doesn’t really matter. This is the opposite of what people are told when they are encouraged to register, but it is true. Elections almost never come down to the line enough that one vote is statistically significant.

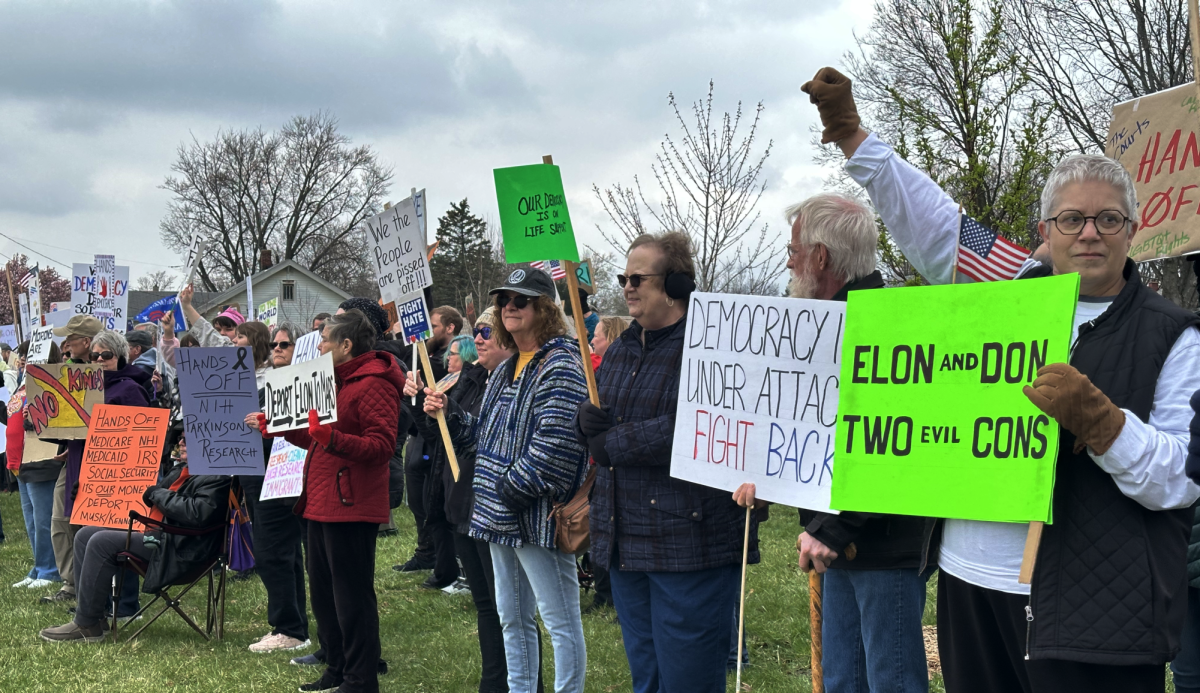

But the college generation as a voting bloc is significant.

Someday, this generation will be the dominant part of the electorate, and the more they vote now, the more they will vote later – since voting is habitual. While the increase in voters may not dramatically shift the outcomes of any specific elections now, it would impact what issues and policies politicians chose to focus on.

“If you had a large influx of youth voters, both parties would have to do something to try and attract them,” Civettini said.

Parties and candidates react to who is participating in elections, and the younger generation has different priorities than older generations. If all college age voters were mobilized, the politics would start to reflect this.

“Anytime the electorate shifts in some meaningful way, both parties are going to shift strategically because they’re just trying to get one more than the other side,” Civettini said.

Because it’s not about winning the majority, it’s just about having a bit more than the other side, parties could focus their energy on different voting blocs, which could change party priorities accordingly. Voting is linked to other types of political participation as well.

“[Voters] are more likely to write letters to politicians. They’re more likely to participate in rallies. They’re more likely to join organizations that lobby for change in whatever way they see fit,” said Civettini.

In short, the more students vote now, the more will vote in the future, and, as Civettini said, the more voters,“the more robust the democracy,”. the United States will have and the more the policies will reflect the next generation.