Poetry swirled in my head as I left the prison.

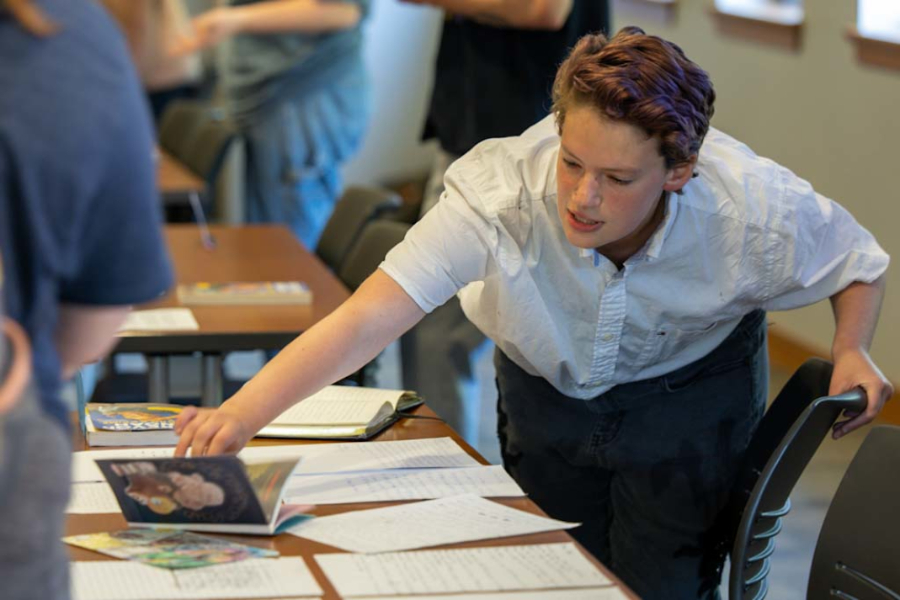

It was our penultimate class last spring term. We had just rehearsed our final presentation to be shared with President Andrew “Andy” McGadney in the following class. Walking through the parking lot, amidst all the feelings that normally come from getting to leave when half our class cannot, I couldn’t stop thinking about the ending of a piece one of my classmates had written.

To protect his privacy, I won’t tell you his name. I’ll tell you this: he is one of the most thoughtful people I’ve ever met. He is a talented writer, a strong and gentle leader, a brilliant thinker, and a mentor to many.

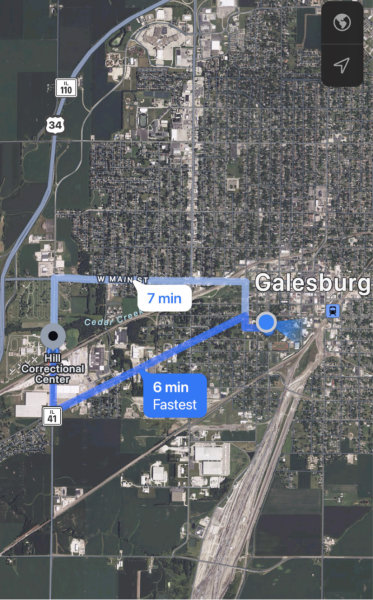

He is also incarcerated at Henry Hill Correctional Center, which is a medium security men’s prison just a six-minute drive from the Knox College campus.

I am part of the second cohort of the Knox-Henry Hill inside-out class. Every Friday in spring term, we gathered in a circle in the prison’s Classroom 3: a group of Knox students, who we call outside students, and men who are incarcerated at Hill, who we call inside students.

In 1997, Temple University Professor Lori Pompa took a group of students to a state prison in Pennsylvania. After an hour-long conversation about justice with a group of men who were incarcerated there, a man named Paul Perry suggested they continue to engage in discussions through a semester-long course. This became the inside-out class model, where traditional college students and incarcerated students take the same class together.

One benefit is that it allows for connections that would not otherwise occur, as the students would probably never have met each other if not for the shared course. Because people’s experiences differ due to factors like race, economic class, gender, and more, inside-out classes challenge everyone involved to grow understanding and empathy for people whose identities and experiences differ from their own. The aim of the class is not to ignore or gloss over these differences, but rather to gain new perspectives, learn from each other, and build community through our shared humanity.

The Knox-Hill inside-out class last spring term was focused on restorative justice, which means addressing harm in ways that emphasize the root causes of the harm while engaging all parties involved. In class, we discussed elements of restorative justice through books and film, and we role-played in restorative justice circles.

We also shared poems and stories—about our lives and experiences, and also about what being in this class means to us. As we progressed through the term, I found it moving and meaningful to hear the impact this class had and continues to have on students.

Inside students expressed gratitude for Professor Leanne Trapedo Sims, for believing in them and putting in the work to create and advocate for Knox’s prison education program. The program includes not only the past two years of inside-out classes, but also courses for inside students taught by Knox professors—so far, Creative Writing, Spanish, and Art.

The men who participated in the inside-out class said that being in these classes and talking with Knox students helped them learn from new perspectives and enrich their education. It also gave them comfort and social interaction, something they rarely get from people outside the prison.

At the same time, I have learned so much from the men. I have seen how resilient and courageous they have had to be in fighting for their education. In the stories they shared, I have glimpsed, from my immense privileges, some of the struggles they have faced within the systems of oppression this country perpetuates. I have learned from all my classmates, inside and outside, about resilience, accountability, and community.

On the last day of class, Trapedo Sims gave everyone a certificate for completing the class. I was moved to see how proud everyone looked celebrating what we accomplished together, the connections formed, and the moments we will continue to hold onto long after the class ends.

For me, the certificate felt symbolic. After all, I am getting academic credit for taking the class. We Knox students see the class listed on our transcripts, can count the class towards our degree, and can even have it fulfill the “immersive experience” requirement that we need to graduate.

For the Hill students, that certificate is the only outside record they have of their contributions to the class. They are not receiving credit towards a degree.

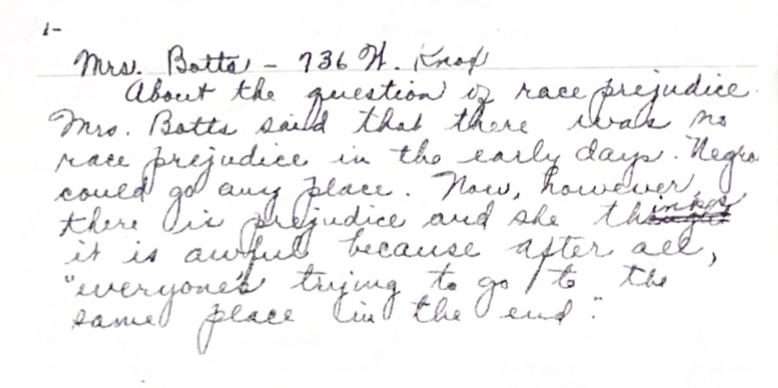

At the end of his poem, the classmate I mentioned earlier wrote about how he hopes he can have his efforts recognized through academic credit. He has taken Knox classes for several terms, including inside-out classes the past two years and other Knox classes offered inside, like creative writing.

On our last day at Hill, President McGadney joined our class. He listened wholeheartedly and empathetically to everyone share their pieces in the circle, and he shared his own stories, too. He acknowledged and embraced the connection between Knox and Hill and the potential to grow the program in the future. I am grateful that he took the time to come. I think his visit meant even more to the inside men.

It is time Knox’s prison education program expands. My classmates and I hope that more inside-out-style classes will be offered in the future, beyond the Peace and Justice Program. Also, we hope to see more classes taught at the prison, like the ones professors Trapedo Sims, Fernando Gomez, and Gonzalo Pinilla taught inside.

The growth of this program cannot happen overnight. Resources and time constraints, especially for the professors teaching these classes, is a challenge. Professors are already incredibly busy, and it’s a lot to ask them to go through prison education training and create classes inside. I understand that without a very wide interest from Knox students and professors, it’s hard to justify investing money and time into a program like this, especially if the benefits are not directly visible.

I hope the benefits can be seen, though.

Earning a degree can make it a little less difficult for someone to find a job after returning from prison. The more likely you are to find a job, the less likely you are to go back to prison. Many colleges and universities already offer degree programs for incarcerated individuals, who can use Pell grants to pay for tuition and other costs. Education programs have been proven to reduce recidivism rates.

Furthermore, about 95% of incarcerated individuals will return home. When someone has access to education inside prison, it not only benefits that individual, but it benefits the community that person will return to and everyone that person will interact with.

Everyone has the right to an education. Regardless of our backgrounds, our resources, our circumstances, and our choices, we all deserve the chance to learn and grow.

As Bryan Stevenson wrote in his book, Just Mercy, “Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.”

Knox has already shown a commitment to educational equity by allowing the inside-out classes to begin. Without Knox’s support, these classes built through Trapedo Sims’ dedicated work would not have been possible, and I thank the institution for its support of the prison education program so far. In the future, I hope that every student who passes Knox classes can earn Knox credit, whether the course was taught on the Knox campus or inside prison walls.

This can be the start of what I hope eventually becomes a full bachelor’s degree program offered at Hill Correctional Center. While I know it will take a lot of work, time, and resources, Knox College can and should play a role in making it happen. Knox is in a unique position that many other schools are not: our nearest prison is six minutes away. This is an opportunity to build a stronger connection between Knox and Hill. People at both institutions would benefit from such an investment.