Walking inside I knew instantaneously that Kendrick’s GNX album was not the mood photographer Sandra Louise Dyas was going for in her Tangled Up In Time show. I switched over to some jazz music I had on hand, and got quickly lost in the simultaneously playful and timeless photography.

Portraiture and beautiful serene landscapes greeted me, and it was apparent that within each photo, Louise Dyas captured what she mentions in her artist statement as the Japanese term “mono no aware.” Louise Dyas describes it as “the pathos of things,” the impermanence of things, and how life is constantly changing. It’s clear by looking at her photographs that the sense of melancholy she feels toward this idea is captured through her lenses almost like a film atop the photo.

Yet, despite this sorrowful mood, there is still playfulness throughout the entire gallery. A solitary grumpy cat, photographed atop a stool in a field. The carnie for a balloon dart game unable to hold back a smile. A chicken gracefully attempts to flee from a woman’s hands as her hair is blown in the wind. A sweet, almost lighthearted play to things. Silly.

That silliness carves out a spot for itself amongst the more somber pieces, and does not shine through in spite of them. In fact, it plays off and works in tandem with the photos surrounding them. Portraits of people in their environments, good or bad. A lived situation where these more playful photographs remind you of how that joy and severity ebb and flow in and out of each other.

My preference in photography has always been and likely always will be for candid pictures. Yet, despite the obviously posed and planned nature of Louise Dyas’ photographs, they feel natural. The people within them are real and so is their world. I can walk into the frame and reality will continue onward from that moment. A fleeting second captured thousands.

It reminds me of one of my favorite words: “sonder”, which is when you realize that everyone around you has a life unique to yours, that they consider themselves to be the focal point of their world, just like you do.

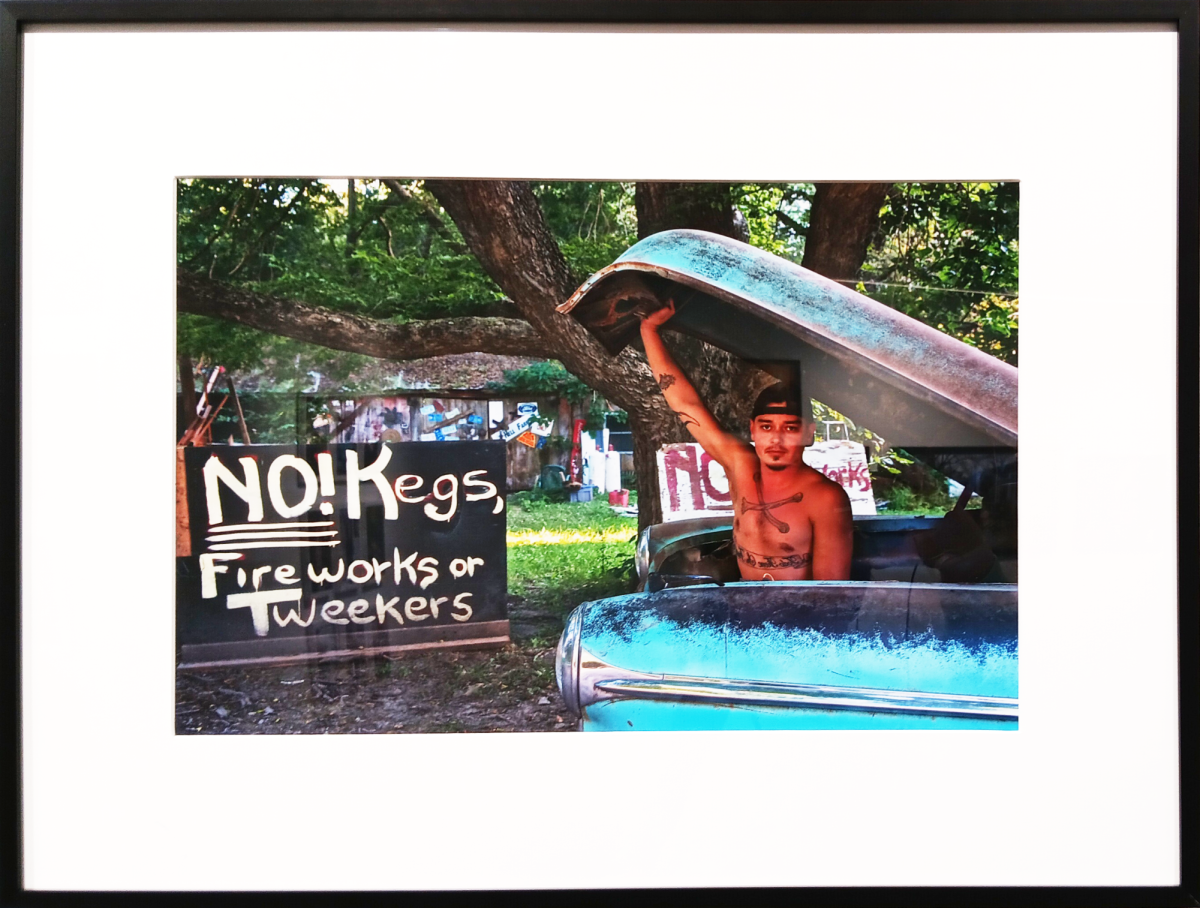

I do not think I have gotten this lost in a Borzello show since perhaps Lynette Lombard’s SPIRITS OF PLACE, or the Knox In New York exhibit. All I wanted to do was sit and stare, despite the commitments I had for the rest of my day. Experience another moment more. Consider and ponder the circumstances of that photograph. What compels one to have a giant hand-painted sign in their yard that reads ‘NO! Kegs, fireworks, or tweakers’?

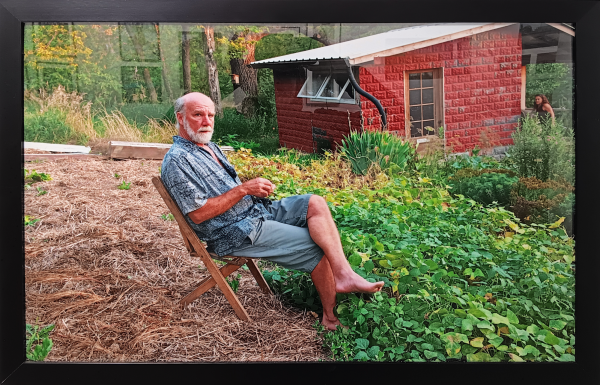

Never have I been so aware of the arrangement of a gallery as I have in this show. I have done some interior design work, hanging artwork, and planning out a room beforehand. It involves a lot of thinking about the relationships and conversations occurring between the pieces present. There is a strong presence of a curated hand in the display of Louise Dyas’ photographs, in some ways creating their own new narratives thanks to their combination. Thanks to the presence of diptychs like The Blue Chair, there is a constant encouragement to ask oneself about those ties.

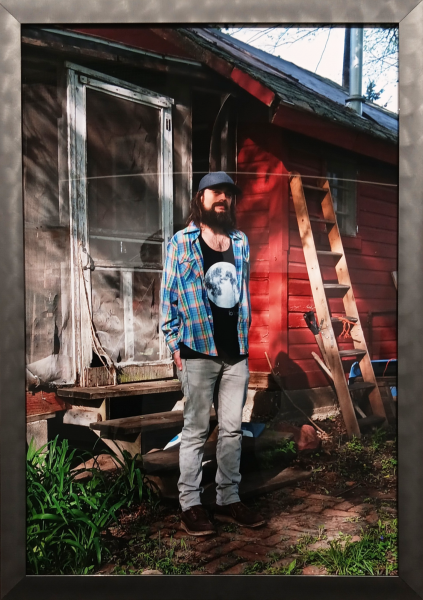

The majority of these photographs take place in Iowa, Louise Dyas’ home state. Perhaps it is my own midwestern heart resonating or my recent obsession with photographs of the Midwest environment, but there is a unique feeling the Midwest has in photographs.

In a day and age like today where it is impossible to truly be isolated from each other thanks to the internet and our hyperconnectivity in society, rural life feels so disparate. Part of it is the way rural midwestern America shows the signs of capitalism in its environment the strongest. Your clothes come from Target but you still work on a farm. The town centers are acres of parking lots, stores, no sidewalks, and maybe a single tree. You have every major chain and business right off the six-lane highway but the hospital is a forty-minute drive.

Having grown up in Chicago and later in life in rural southern Indiana’s tiny little Boonville, and now being in Galesburg, these things shine through in midwestern culture stronger than saying “ope” and hour-long goodbyes do. These people have old rusted cars on their lawns and live in partially busted houses and they use a phone just like I do and go eat at McDonalds every day because it’s the best restaurant in town. It is a dichotomy that makes midwestern people feel constantly juxtaposed to their environment and Louise Dyas pulls that juxtaposition out of her photos as easy as water.

Now, I sit here writing this, with Tottomori’s Sproutpup album playing, and all I want to do is capture time the same way Louise Dyas did. I am graduating at the end of this spring term. While I am always reluctant to reach for a camera, I am starting to think that just staring at my friends as we share the last few months together in an attempt to burn their image into my brain won’t cut it anymore. Perhaps I can just start with actually doing my BeReal every day.