Some of you may stop reading when I tell you this review is of two books from Palestinian authors whose work represent the reality of what Palestinians go through. Perhaps our world is so plagued by privilege — the ability to shut down and refuse to acknowledge knowledge of an active genocide and go on with our lives — that westerners will not even bother with literature from ‘less worthy’ parts of the world.

These places are less worthy because the people living there are not white, have limited resources or simply because they are different from Americans. Which is why the West is able to ignore the lives being lost in those same countries. We can start by empowering the work of Palestinians and making sure everyone hears their stories in a world that is trying to silence them.

I read Against the Loveless World back in June and I was shocked by the way Abulhawa crafted Nahr’s character with an amiability that made me feel like I was meeting an old friend, while also creating the image of a powerful freedom fighter who would refuse to give in to Israeli colonization.

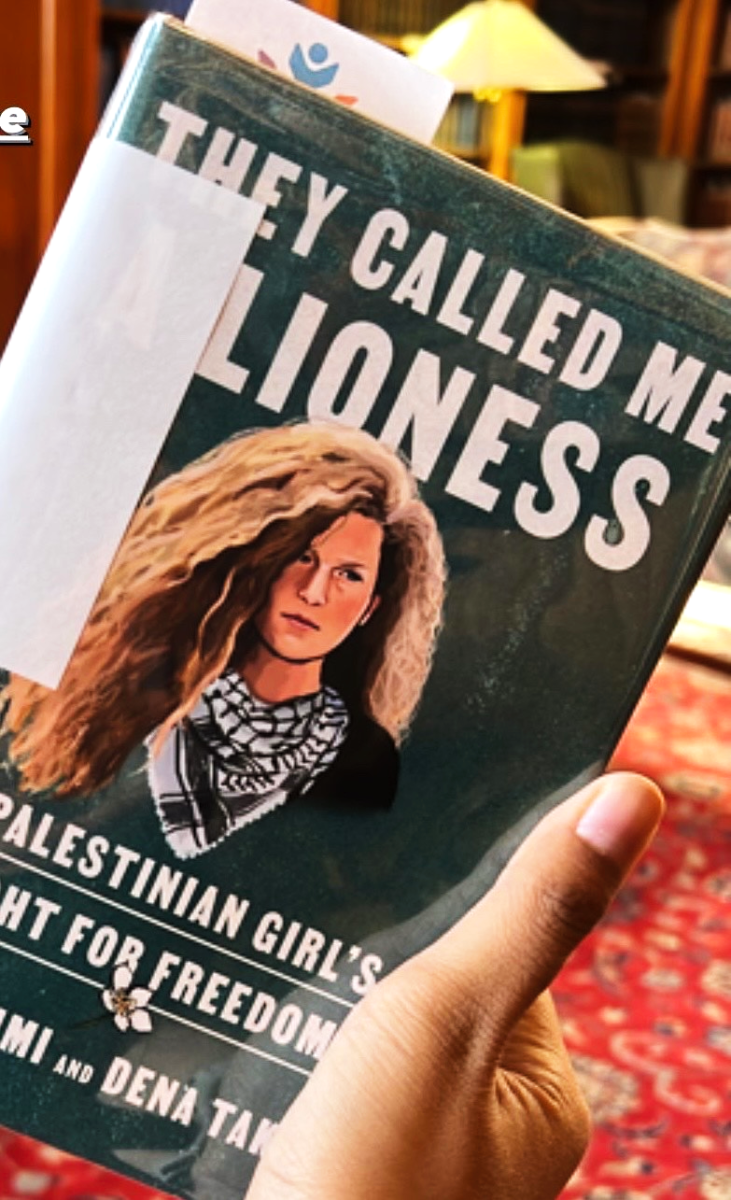

Awestruck by the ability of Palestinian writers to narrate stories of genocide and colonization with a painful beauty unlike any other literature, I read They Called Me A Lioness. It is a true story of a Palestinian teenager who had the audacity to meet an armed Israeli soldier with a slap: an act of relentless courage that became an important symbol of Palestinian resistance. After all, slaps and stones can do so little against tanks and nukes: a dichotomy Takruri conveys in her narration of the day to day injustices faced by Palestinians living in Gaza and West Bank.

Nahr’s displacement and her journey from Kuwait to Jordan and then Palestine, where she eventually gets locked up in the “cube” (an Israeli prison cell) leaves the reader with a lingering feeling of homesickness. Abulhawa memorably conveys this feeling when she takes Nahr to Palestine, and she enjoys the dish of Mansaf: consisting of spiced lamb with rice and yogurt, which reminds her of holidays from her youth where she would enjoy the dish with her family.

“…I knew I could never again be complete in one place. This was what it meant to be exiled and disinherited-to straddle closed borders, never whole anywhere. To remain in one place meant tearing one’s limbs from another. I missed my mother. My brother and grandmother. I balled a bite of mansaf in my hand and looked around the room. Bilal, Jumana, Samer, Wadee and Faisal, other friends, Hajjeh Um Mhammad and her sisters, neighbors, and more family. This was where I belonged, but so much of me was still scattered elsewhere,” Nahr says, as she is finally able to be in Palestine, a country which was meant to be her home, but she had only heard of in her grandmother’s stories and on the news.

Nahr’s sense of displacement is similar to Tamimi’s feelings of frustration within They Called Me A Lioness. The frustration is obvious from her mention of being able to see the sea but not being able to visit it because of checkpoints and armed soldiers placed by settler colonizers. This feeling is poignantly represented in her question to her readers, which is almost a plea for people to care about the plight of Palestine.

“What would you do if you grew up repeatedly seeing your home raided? Your parents arrested? Your mother shot? Your uncle killed? Try, if just for a moment, to imagine this was your life. How would you want the world to react?”

The conflict going on in Palestine is very real. Homes are being bombed to the ground, and mothers and uncles are being killed. For many, this is not imagination. Why is the world not reacting?

Winner Honorable Mention Critical Review Illinois College Press Association