Much of the United States will see a total solar eclipse, but Knox will only see about 96% coverage according to Associate Professor of Physics Nathalie Haurberg. The next solar eclipse in the US won’t be until 2044, and will not be visible from the Midwest.

“It is worth viewing,” Haurberg said.

The Department of Physics and Astronomy is hosting an eclipse viewing event on Monday, April 8 on the softball fields.

The department is hoping to set up telescopes so students can better view the partial solar eclipse. The eclipse will be projected on a screen, and a telescope with an eye piece will also be available.

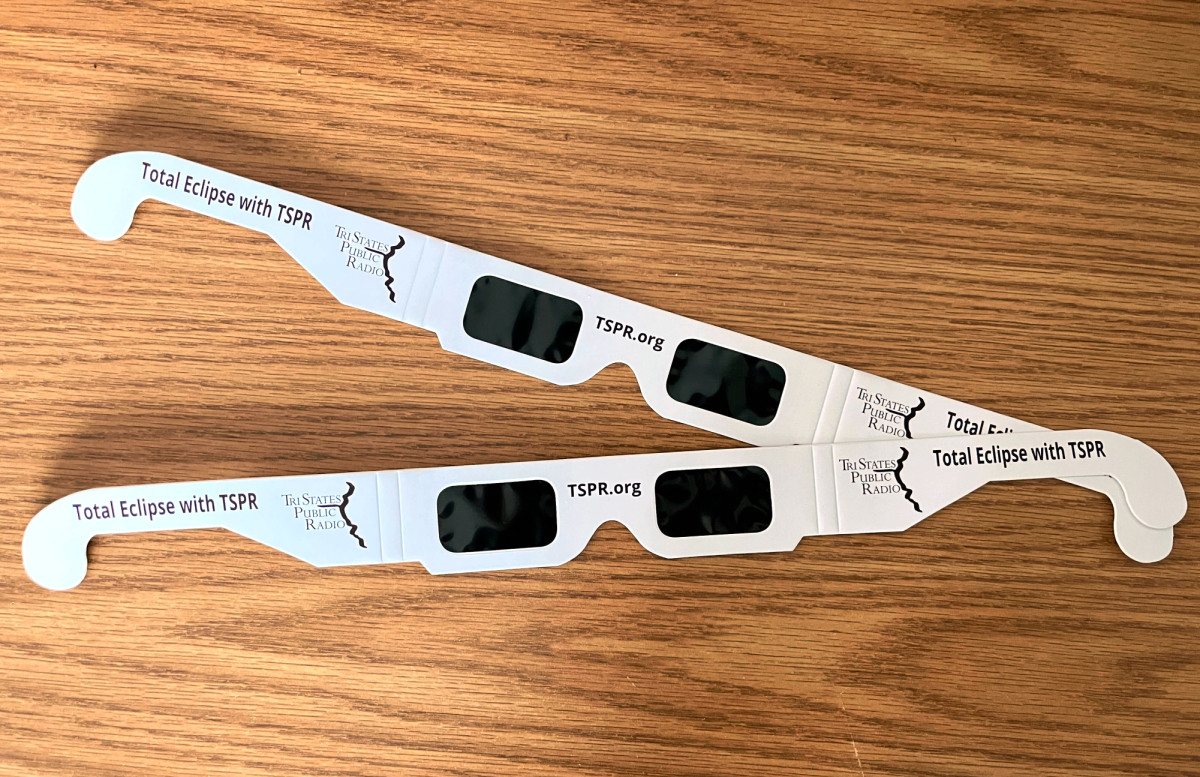

The eclipse starts at about 1 p.m. and is expected to peak around 2 p.m, although if it’s raining or cloudy, there might not be much to see. The college will be passing out eclipse glasses for viewing, as it is dangerous to look directly at the eclipse.

Haurberg says this eclipse is making such big news because so much of the country will be able to view it. Solar eclipses are fairly frequent, but they are not often viewable from here.

“When solar eclipses happen, the path of totality is a relatively small swath of earth, and that small swath could go anywhere,” she said. “A lot of times it goes over the ocean.”

For a solar eclipse to occur, the Sun, Moon, and Earth must be in perfect alignment during the new moon phase. This is why there’s not a solar eclipse every month.

Scientifically, solar eclipses are exciting. They give astronomers the chance to study things they can’t study normally.

In 1868, a french astronomer traveled to India to view a total solar eclipse. There he discovered helium in the outermost layers of the sun, a previously unknown element.

Those outer layers, now called the chromosphere cannot be seen normally, the light from the rest of the sun blocks it out. But during an eclipse it can be studied.

Scientists can also study really subtle effects of gravity, says Haurberg. Starlight that passes by the edge of the sun is bent by gravity, an effect of Einstein’s theory of relativity.

“We can study the starlight that’s passing very nearby the sun, which we normally can’t study because it’s basically blotted out by the sunlight,” she said.

Haurberg herself is traveling to her graduate school alma mater Indiana University to view the total solar eclipse.