Conversations about the experience of students of color at Knox resurfaced after the March 6th protest against sexual assault when students of color came forward to highlight how racial and national identities impacted students of color’s experiences on campus.

Students of color at Knox such as sophomore Precious Odejimi, are determined to continue to advocate for themselves and make sure their voices are heard.

“We are here to stay,” Oedjimi said, referring to the March 6th protest, which allowed for conversations surrounding race relations at Knox College to resurface as students of color stepped forward to highlight how conversations around sexual assault are incomplete without discussing how racial identities impact victims of sexual assault on campus.

Up to 80 students collectively stormed the faculty meeting going on in Alumni Hall to protest the prevalence of sexual assault culture at Knox.The conversation then expanded to address the intersection of race and nationality, which impacts many survivors of sexual assault and students at Knox. Knox prides itself as “one of the 50 most diverse campuses in America,” as 33% of students at Knox are people of color or people with diverse racial backgrounds and 19% of students are international students, according to the official website. The protest led some students of color to question whether the college truly supported the experiences of students with diverse racial backgrounds.

“I talked about sexual assault. That was the first thing that came out of my mouth. But I have to talk about my blackness too. ABLE (Allied Blacks for Liberty and Equality) was dealing with our own personal things a weekend before and we never got people standing up and going to campus life for us. At Knox when talking about sexual assault the perpetrator is likely to be white and male. Why is it that in the Title IX Office we don’t have anyone of color? How much more comfortable would I feel to report my sexual assault if I had someone look like me?” President of ABLE and senior Isaiah Simon said.

Simon spoke in reference to the weekend of February 25th when a Campus Safety officer allegedly stormed ABLE house at 12:30 AM to shut down the Mardi Gras party which was held to commemorate Black History Month, due to noise complaints. When students reminded him that the registered party was meant to be shut down at 1 AM, he left. He returned a short while later pointing flashlights at the students and allegedly threatening to call ‘COP’.

“In terms of the party, we are seeking justice. Investigations are being made around Campus Safety as well as why we were shut down and why certain groups have more privilege in getting things approved and not being shut down, as compared to other groups,” Simon said.

Some students such as Odejimi and student from Ghana sophomore Agnes Azalimah even felt that events such as those that transpired at the ABLE party were a part of a larger problem of lack of support for students from diverse backgrounds. They felt that lack of inclusion of students of color, especially from African countries, has been evident even before the incident at ABLE, and is manifested in their daily experiences.

Students like Odejimi, who is an international student from Nigeria, said she felt that Knox used African students as “diversity pawns,” during Black History Month, by posting about ABLE and Harambee on their Instagram, but not directing resources to support these clubs.

“Diversity means many things, and diversity in one direction is not diversity,” Odejimi said.

Azalimah discussed how the International Fair (I-Fair), the annual week-long series of events to commemorate international students and their culture, drew her to come to Knox. However, she recalled being disappointed when she realized that I-fair was not open to including all communities.

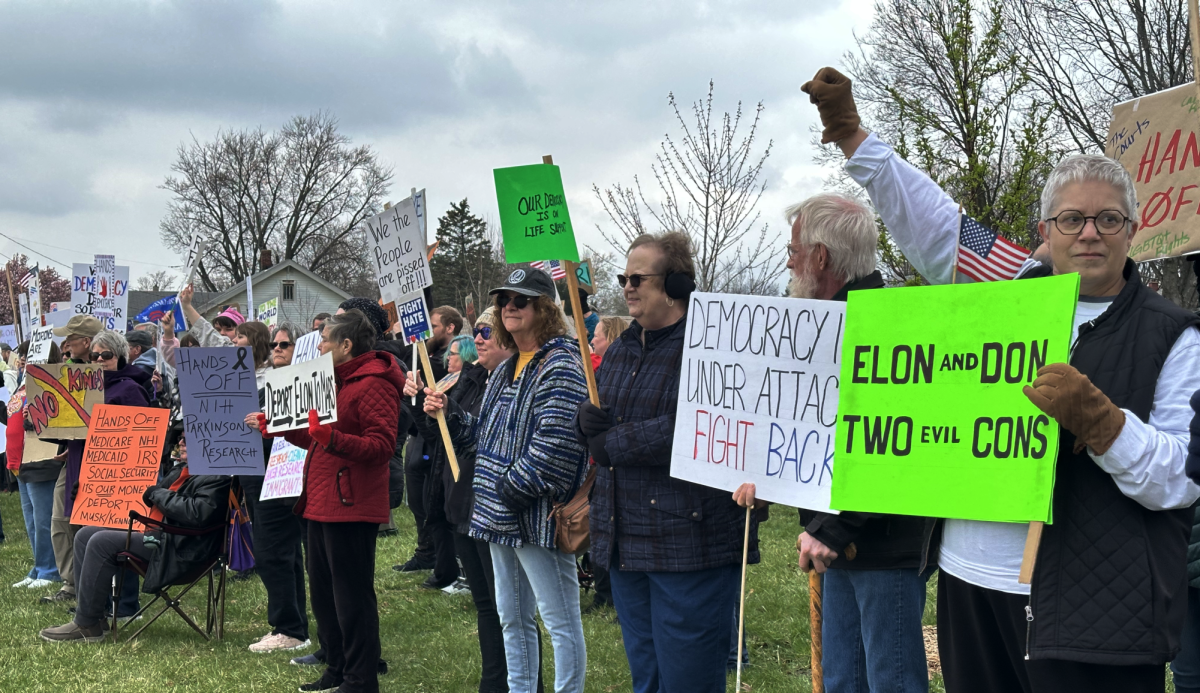

Agnes Azalimah and Precious Odejimi at I-Fair

“Knox’s idea is I-Fair, waving flags, showing a big community of different flags. The thing is that there is no inclusion at Knox. We have maybe 50+ flags but are we really inclusive? Part of that includes having more people who look like us. You would have to work harder for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) if you don’t recruit more people. They do not come to African countries to attract African students to Knox,” Azalimah said.

Simon, Odejimi and Azalimah all said they felt that inclusion can be brought about by supporting cultural clubs on campus, who strengthen the voices of people of color and allow them spaces to express their identities safely and comfortably. Being leaders and members of cultural clubs, they feel that not enough resources are being directed towards empowering these spaces led by students of color. Students such as Simon also said they felt that the lack of support for their diverse identities fundamentally threatened Knox’s values of diversity, equity and inclusion for these students of color.

“We students have to ask where is our money going to. We have to ask that question. If cultural clubs are maintaining students, creating safety, creating space for DEI, then my question is why isn’t our money going to these cultural houses?” Simon said.

Simon, Odejimi and Azalimah said they felt that cultural clubs are particularly important to fund because they are important to foster the community of culturally and racially diverse students, who do not have similar spaces elsewhere on campus.

“Cultural clubs open up the avenue to have uncomfortable conversations, but people don’t want to feel that so they don’t show up. ABLE, Movimiento Estudiantil Chicanx de Aztlan (MECHA), Lo Nuestro, and Harambee show up for each other,” said Odejimi.

Cultural clubs have been particularly important for students of color because they have allowed them to form communities that help them navigate their unique identities, and advocate for themselves. Senior Manny Pino Oviedo emphasized on how the community of people of color show up for each other.

Isaiah Simon, Valeria Aguilar and Manny Pino Oviedo at the March 6th protest.

“Me and Isaiah have been here for a while and community has a generational impact. I have all these experiences: I’ve been a part of this and that and what are pieces of information or traditions that I can pass down and model the moment when the time calls for it.” Oviedo said, referring to a photo of theirs with Simon and junior Valeria Aguilar, from the protest of March 6th.

At the protest, Simon, Oviedo, Aguilar, Odejimi and Azalimah all showed up to express their discontent at the culture of sexual assault, but they felt the conversation was incomplete without talking about how their race and intersectional identities influenced their experiences. However, as they entered the faculty meeting, several of them felt discomfort and noticed microaggressions that further uncovered deep-rooted systemic issues such as institutional racism.

“Something that enraged me passionately was when Isaiah and Manny went to the faculty meeting at Trustees for the protest, they were asked what they were doing there as if they didn’t belong there,” Aguilar said.

Simon reported feeling like some voices were being heard more than others, which proved to Simon that the needs of POC are not prioritized the way they should be, especially because POC have to navigate the burden of racism alone, when cultural clubs are not being adequately funded.

“I watched (people’s) body language change. I do feel like certain voices, when we talk about the nuance of racism and race, white voices were heard more than POC’s. When my white peers would talk at a higher octave, it wouldn’t be seen as aggressive, but when I did that it was like I was trying to endanger someone,” Simon added.

Even within a space such as the protest where students of color came out to advocate for themselves, Odejimi, Simon, Aguilar and Pino Oviedo all reported facing microaggressions, which made them feel unheard in comparison to their white peers.

“I was called another black girl’s name, but didn’t correct at the moment as we were trying to present a united front,” Odejimi said.

Nevertheless, the protest offered some hope to students of color that real change can transpire. Students such as Oviedo looked positively at the impact it generated and the ways in which it empowered students of color to express their issues out loud before the administration. Despite the progress, some students of color such as Oedjimi feel that there is still little action being taken to address their concerns and provide support along the true lines of Knox’s values of diversity.

“I am a realistic person. How can I feel hopeful if someone on my floor has confederate flags in their room? If people are not willing to change their POV, it feels like throwing out noise into an empty space.” Odejimi said, when asked about her hopes regarding the future of students of color on campus.

The lack of hope reflects the burden of being a person of color who is involved in activism on campus. But even beyond Knox’s campus, Simon was positive that Simon’s actions were motivating black people to be hopeful of the future and feel seen in Galesburg.

“There was a student in Galesburg and he told me, ‘I love when I see you walk on campus,’ and I was like why, and he was like, ‘you’re actually showing me that I can go to college and be happy.’ He can have joy. He can enter white spaces and be happy,” Simon said, when talking about the importance of directing joy at creating change.

Many students of color at Knox all feel the need for their voices to be heard and for the community to unite to unlearn its biases so it can create a healthy and welcoming culture that is true to the meaning of DEI.

“Knox is an institution of learning, it should also be an institution of unlearning. Actively listen and then work to change. You shouldn’t be ashamed of learning new things. Everyone is born racist because of the world we are born in,” Aguilar said.