Senior Ellie Jacques shares her experience of being “in the gray”.

From first grade until her high school graduation, Senior Ellie Jacques was always picked to speak on Martin Luther King day to represent the entire Black community in her school. By the time she reached high school, she stopped responding to her teachers. Being biracial, Jacques shared that. she never felt a part of the Black community and questions how she’s supposed to talk about Martin Luther King Day when she’s always been singled out.

“I identify as ‘other,’” she pauses, “in a lot of stats, you choose—either you’re black or white, and if they don’t have a mixed option or biracial option I choose other,” Jacques said.

Born to a white mother and a Black father, Jacques was adopted by a queer couple, Helene Jacques and Regina Miner when she was 4 days old. During the three days that Jacques’s birth mother was in the hospital, her parents were worried she was going to change her mind.

“We worried about her bonding. But she didn’t, she kept her decision,” Miner said.

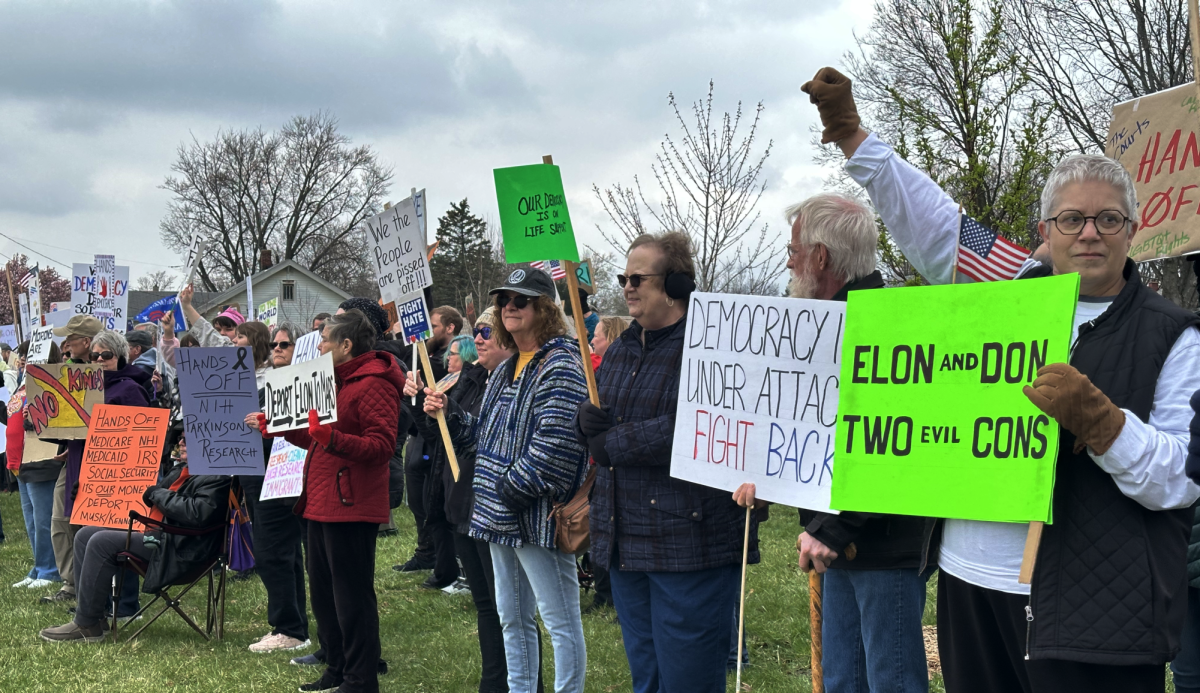

Ellie Jacques (L) with her half older brother Matthew Johnson ( R ). Courtesy of Ellie Jacques

“She gave me life, she gave me DNA, but that was it about our relationship,” Jacques said, sharing she lost her grandmother in 2019 and her birth mother in 2021.

In the world of black and white, Jacques has felt out of place; she’s always found herself in the gray. On a recent census, she had to choose black and then white when asked about her race and ethnicity.

“My race is mixed and my ethnicity is also mixed,” she emphasizes. At the beginning of her education, there were just a couple of students of color in her class, so she’d received comments on how different her hair was and questions about whether people could touch it.

Her parents often tried finding out about the birth family but had no luck. In 2018, (Helene) Jacques made an ancestry account to help find out where her daughter’s birth family is from.

“My dad was Black, but I didn’t know where he originated from. Most Black people in the diaspora don’t know where their original family is. Having this piece of information was mind-blowing to me, that I’m a big percentage of Nigerian and Congolese.” Jacques said. He died when she was two years old, leaving her with no memories of or about him.

Within the span of four years, Jacques has been able to locate her father’s sister, her older half-brother, and an older half-sister.

You have your father’s eyes,” Ellie’s aunt commented the moment they met. Since then, she’s been welcomed with open arms by her birth father’s side of the family.

Ellie Jacques (L) with her aunt Shyrl ( R ). Courtesy of Ellie Jacques

Jacques shares a memory of a Naperville resident giving a two-minute speech on Harriet Tubman that made her teachers uncomfortable. She recalls not making a greeting card for father’s day when the entire classroom was decorating stock cards with glitter, fingerprints, hearts, and “I Love Yous”. She would sit back and look at all the kids who lived in a “perfect” world.

“It was the underlying tone of racism and homophobia; teachers didn’t know what they were doing,” Jacques said

Jacques’s parents recall being in the grocery store for their usual food supplies, stocking on items for their pantry, when a woman came to them and asked if their daughter was a foster child merely because she was biracial,

“Ellie’s birth mother [had] blonde hair, blue eyes, she could’ve been my child.” Helene rolls her eyes.

“I’m Black,” Jacques pauses, her eyes speaking of confusion and sadness. “But, I’m not,” she whispers, her voice breaking.

Despite the hardships the family faced, Jacques, is now finishing her last year of college as an Africana studies major, and a Gender and Women’s Studies, and Anthropology-Sociology double-minor at Knox College, with her mothers working nearby in Naperville.

“They did the best they could with whatever information they had when living in a racially segregated society. Growing up in a queer house as a biracial kid, they prepared me for the long run without even knowing it,” Jacques said.