In 1852, Knox Academy, the secondary school once associated with our college, graduated a man named Jeremiah Goldsmith Anderson. Anderson, a young abolitionist, later joined John Brown’s radical anti-slavery militia which in 1859 raided an armory in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. Their objective was to start an armed slave rebellion in the South. Famously, they failed. Jeremiah Anderson was killed in battle and John Brown and his followers were put to death. But they would be remembered. They were memorialized in a marching song, “John Brown’s Body,” that was beloved in the Union throughout the Civil War, and the story of their sacrifice continues to inspire people today.

Our college’s history is peppered with episodes like these. You don’t need us to tell you. The admissions brochures, the college website, even the speeches and emails of our senior administration—it’s impossible to go very long without hearing about Knox’s ties to the abolitionist movement of the 19th century. We come from a heritage of advocacy for radical social change. Many of us wear that heritage like a badge of honor. We think not only of the antislavery movement, but the various social movements of the 20th century—the civil rights movement, the movement against the Vietnam War, and so many others—that captured college campuses by storm. When many of us begin college, we imagine that we are joining a community that reaches across vast stretches of distance and time. This is the community of college-aged organizers that have worked toward radical social change over the years. We fill our heads with the striking and beautiful images of the 1960s that were printed in the schoolbooks of our youth, depicting people coming together to fight against all forms of social domination. After we arrive on campus, however, we often find ourselves disappointed by the current reality. It isn’t the ‘60s anymore. You would be hard-pressed to find someone who sees our college, as it stands today, as the cradle of a radical vision for society’s future. Rather, many of our thoughts about this school today begin and end with the fear, however fully-realized, that it is little more than a vampiric institution bent on shackling us to decades of student loan debt.

That is not to say that organizing does not take place on this campus. It does—and we should all be thankful for it. Only, it takes place despite the social conditions we inhabit, rather than being nurtured by those conditions as it ought to be. The few students who take on the burden of organizing at this school today are typically those impacted by the situations of harm against which they themselves are organizing, which often originate from the Knox community itself. For example, we can think of our queer students and our Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) students who, over the recent years, have struggled for basic respect from the administration and the student body alike. They have leapt into the jaws of a gargantuan administration that dwarfs them in size and strength. Likewise, they have stared into the unblinking eyes of the indifferent majority of white liberal college students who never fail to adorn themselves with the language of social justice, but who vanish into thin air whenever they are presented with the opportunity to engage in real transformative work.

The marginalized students who organize on our campus today are endlessly brave. No one can dispute this. But they should not be shouldering the burden of organizing alone. Instead, it should be the norm rather than the exception that a Knox student organizes for radical social change. This community should be awash in waves of solidarity that harken back to the coalition-building of student movements past. Those students wrote, sang, chanted, and resisted their way into the history books, and we love them for it. But the art of building coalitions as broad and strong as theirs, it seems, has been lost. Where did that art go? Did we lose it, or was it taken from us? We could point to a number of likely culprits, both on and off campus grounds. On campus, students have been faced with an explosion in the cost of attendance that threatens to render higher education totally inaccessible to Americans who do not come from great socioeconomic privilege, and that leaves marginalized students in fear of being ostracized in a community that is proving more insular and alienating by the day. Off campus, state security forces and the reactionary elements in our society have, over the decades, delegitimized radical social movements, obfuscated the histories of these movements, and discredited their leaders (and leaders of color in particular). On and off college grounds, radical energies have been co-opted by liberals who say all the right words but exhibit no commitment to abolishing the racial capitalist system that generates all social and economic exploitation.

Despite all of this, hope for radical social change still sparks here, there, and everywhere across this country, including on college campuses. Many of our generation have been initiated into struggle by way of their participation in ongoing social movements in their hometowns. They received a baptism by fire in the course of last summer, when law enforcement agencies unleashed the full force of their mace, tear gas, rubber bullets, and clubs on a generation of youth who rose up after the lynching of George Floyd by the Minneapolis Police Department. The task before us is to channel these passions and experiences into the campus community, that they might inform our actions and inspire others to break free from the spell of complacency. We must search for a path forward for us all.

With this article, we hope to present the Knox community with one such path. This path speaks to us personally. It leads us to the reinvigoration of our radical spirit as an institution. This is the path of the movement to abolish the prison industrial complex (PIC).

In his farewell address, President Eisenhower coined the term ‘military-industrial complex’ (MIC) to describe the relationship between a nation’s military and the defense industry that supplies it. In naming this troubling alliance, Eisenhower intended to warn and prepare the nation for the effects such an alliance would have on public policy. Later, the term would be ‘stretched,’ or further excavated, by contemporary abolitionists seeking to name and critique the disconcerting overlap between the state and what activist Angela Davis describes as the ‘punishment industry,’ the sector of our economy invested in the distribution and maintenance of surveillance technologies and carceral institutions.

The settler-colonial United States of America operates according to carceral logics that perpetuate and violently uphold white supremacist patriarchal capitalism. These guiding logics are implemented by both the military-industrial complex and its close relative the prison-industrial complex. The PIC—a term coined by Angela Davis in 1997—describes the aforementioned relationship between our government and the industry supplying it with the technologies, employees, and institutions necessary to maintain our police state. As defined by the abolitionist organization Critical Resistance, “PIC abolition is a political vision with the goal of eliminating imprisonment, policing, and surveillance and creating lasting alternatives to punishment and imprisonment.” Abolitionists recognize police and prisons as mechanisms of control and surveillance borne from chattel slavery and settler-colonialism. Such conclusions were formed in part through intensive interrogation of history, tracing the formation of the police back to slave patrols originating in the 1700s. Our understanding of police and prisons as racialized tools of oppression is also informed by overwhelming evidence that BIPOC are subject to far higher rates of imprisonment and police violence than white people. According to the NAACP, African Americans and Hispanics constitute 56% of incarcerated people in the US even though they represent a mere 32% of the total population. Native American men are incarcerated at four times the rate of white men, and Native American women at a staggering six times the rate of white women. A University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee study revealed in 2013 that Wisconsin, which had the highest Black male incarceration rate of any state, imprisoned 1 in 8 of its Black men of working age. It should be clear to all of us that the fight to end racism and anti-Blackness is rooted in the struggle to eradicate the PIC.

Though the abolitionists who founded our college faced substantial criticism for their political positions, such opposition did not deter them, and it should not deter us. Prison abolition is not an easy movement to advocate for, particularly in the country with the highest incarceration rate in the world, but neither was the anti-slavery movement. It is time for Knox to embrace its radical roots and join the contemporary struggle for abolition.

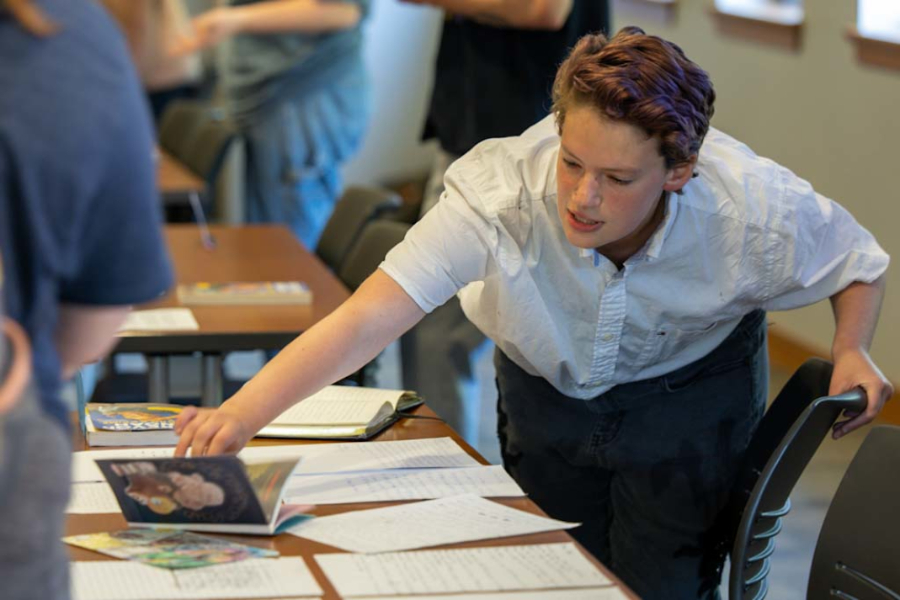

Knox YDSA’s Abolitionist Working Group is seeking Knox students who are interested in becoming penpals with inmates of Hill Correctional Center. We are also proudly bringing Parole Illinois, an inside-outside coalition fighting to reestablish discretionary parole, to our campus on Friday, April 9th. Now through the end of spring term, we are collecting books for donation to incarcerated youth in Mary Davis Detention Center. If interested, please contact us at [email protected].