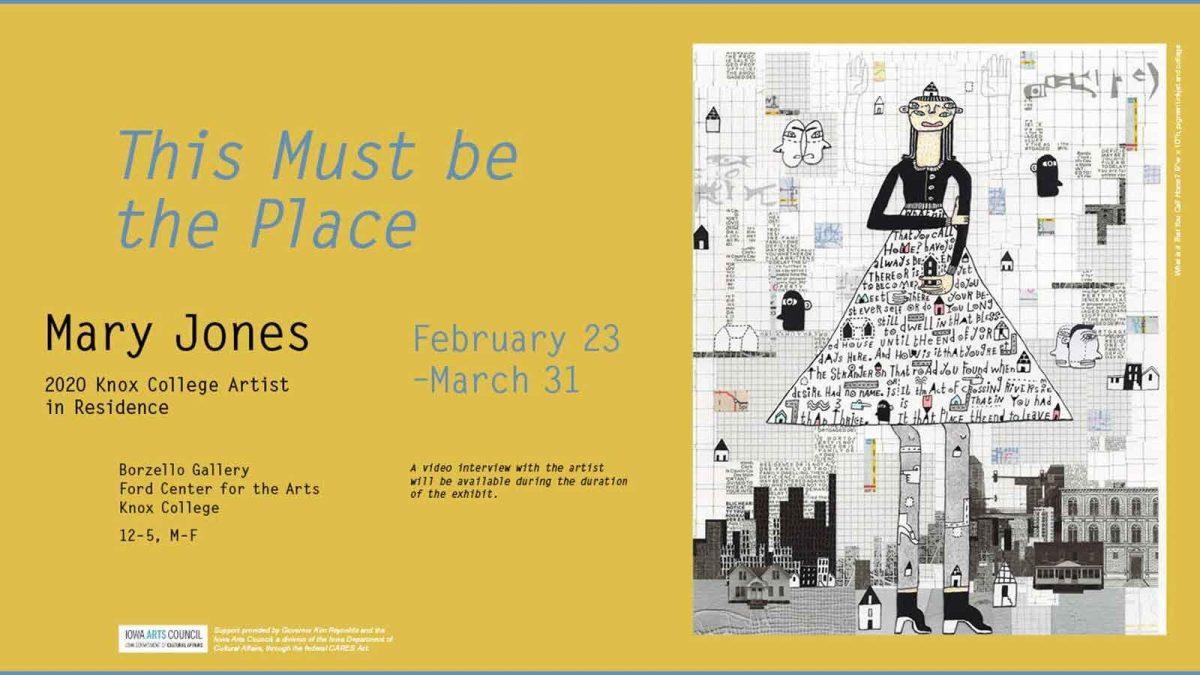

Former Artist-in-Residence Mary Jones has an exhibition in Borzello Gallery running through March 31, 2021. Her work in the gallery is an answer to a question she posed to Knox students: What is it that you call home?

At this time last year, while Mary Jones was the artist-in-residence working with student artists at Knox, I was beginning my study abroad program in Denmark, where my core course was “A Sense of Place in European Literature.” This class had an approach to reading that I found profoundly unique, as well as tedious, at the time. With whatever we read, we were instructed to hold literal maps of the area in the text, and draw on the routes and places of interest of the main character. For texts set in Denmark, we were at times instructed to use our maps to physically walk those same paths.

This class made me acutely aware of my poor sense of direction. It frustrated me at times when I would get lost (mentally and physically), as I was trying to get a degree in creative writing and not cartography. Yet, it eventually opened my eyes to how much I underestimated the impact of place on character development. How the places we inhabit shape us in overt and discrete ways, and we similarly leave our mark on the places that shape us. We become part of a great collage of life that the land we walk on has held. In our class’s reference text, “Atlas of the European Novel,” Franco Moretti argued that “different forms inhabit different spaces.” Each of us has a unique relationship to the places we live and inhabit. When Mary Jones worked with Knox students, she posed to them the question: “How do the inhabitants of a place infuse it with meaning?”

I became more excited to visit Mary Jones’s current exhibition at CFA when I stumbled upon her website, where she wrote that her method of deep mapping aims to capture a sense of place. “In other words, mapping is a way of knowing not only where we are but also who we are in a particular space,” she wrote. “ In mapping where we are, the space becomes a place.” Her words reminded me so much of the concepts I learned a year ago, and so did her exhibition.

Much like her description, most of her work looks at elements of place by mapping, whether from bird’s eye or street views. Using methods such as collage, photopolymer intaglio, and mixed media, there is a lot of layering: annotations with abstract human figures, pictures of buildings, and newspaper clippings often against the background of maps or grids. In her artist interview she mentions Lincoln Avenue in Chicago, knowing that the tracks of her grandparent’s streetcar are buried under the asphalt of that same street she’s walked along in recent years. It’s interesting to dissect the intimacy of that outlook on the space around her, that Lincoln Avenue evokes that image of the streetcar for her in a way that it doesn’t for anyone else.

I find fascinating the universality of our surroundings and how they appear to us especially on maps, but the way that we interpret spaces because of our personal knowledge, histories and cultures is profoundly individualized. Oftentimes Mary’s maps aren’t logistically accurate for people who want to navigate the spaces she’s depicting, but they represent the fragmentation of our concepts of place. We might not know the precise angles of every street corner on our routes, but we know how to get from point A to point B, and often the stretch of land between can fade into the background. For others, the stretch of land between may be where their home resides, and that is the space imbued with intimacy for them, the space that becomes a place. The layers of her work liken land to a canvas, always being painted with time and marks of life or its destruction.

Jones’s exhibition made me reflect on how place can be a tool for understanding not only a piece of ourselves but the people around us. Perhaps too, the importance of having people around us, even strangers, in our own development. At this time last year I had to abruptly leave Denmark, where I was making a temporary home, to isolation in the states because of a global virus. I think that departure has often made me reflect what I was to Denmark, and what it was to me. Jones says in her interview, “Every time we remember, we’re actually rewriting the last memory of that place.”

As a senior, I have spent a lot of time coming to terms with what my college experience has been for me, and naturally a lot of what I have become is an amalgamation of what I’ve been surrounded with. I think whenever I visit the exhibitions in the Borzello gallery, I become strangely conscious of the present, aware that I won’t always have this access to art at Knox because this, too, has been a temporary home.

Mary’s main inspiration comes from flanerie, or taking walks and observing, perhaps without a destination in mind. The closure of public spaces has taken a lot of the natural flanerie from our lives. Some important memory havens in Galesburg, places I would walk to like the Beanhive or Fat Fish for jazz night, are no longer accessible. I think at times I have been preoccupied and in denial over these abrupt losses. I think about new students, and how they hadn’t a chance for these locations to be part of Galesburg for them. I think about what Galesburg will be for me when I leave, if I will remember what it was to me before, or what it has been now.

I think what I was left with after this exhibition was a sense of hope. Knowing that you will leave a place soon, inspires you to make the most of the time you still have. When I had the amazing opportunity to live abroad, I thought I had more time to make meaning. That loss has made me more aware, and thus grateful for the time I have left here. The loss of some spaces has made me more aware, and thus grateful for the spaces that are still here. The loss of people has made me more aware of and grateful for the people around me. It brings me a sense of peace to think: there are many empty spaces in my map of Galesburg that I still have time to color in. There are many places and people still alive that make Galesburg a home. So thank you, Mary Jones, for reminding me.