Every student at Knox — and their grandmas, cousins, aunts, parrots, second cousins, uncles, and fifth-grade math class crushes — has heard about Knox College and Galesburg’s abolitionist origins. It is spoken of in the classroom, in Seymour Library books, and on school websites. However, the local history also contains deep roots of racial discrimination and prejudice, which is not nearly as talked about. From the beginning of the 19th century to the end of the 20th, segregation affected employment, housing, social life, and even recreation for Black residents in Galesburg. This article will show examples of stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination faced by Black residents in the community during that period. But, before I do so, let’s get into the birth of our amazing community in Illinois.

The Birth of Galesburg

It all started with this guy named George Washington Gale. See something here? Gale, Galesburg? The similarity is not just a coincidence. Reverend George Washington Gale had this little thing called the Oneida Institute of Science and Industry in New York, which offered education in exchange for manual labor. His idea was to experiment with young men who were eager to pursue an education but were financially unable to do so. So, in exchange for tuition, the students of the Oneida Institute worked three and a half hours of manual labor a day on the farm, or at the carpenter, trunk, and harness-making shop.

Sure, right now it seems weird, but back in the day, it was actually…pretty weird too. Oneida Institute was not just unusual because of its manual labor policy but also because people were astonished that, there, white men and Black men seemed to be treated equally. Despite the controversy, Gale wanted to create another manual labor college, specifically in the West. That is why, in 1835, he purchased 17 acres of prairie grass and wildflowers (it hasn’t changed much since then..) in what would become Galesburg.

The Knox Manual Labor College

In 1837, the Knox Manual Labor College, or today’s Knox College, was founded. Knox’s roots were, well—very Christian. Earnest Elmo Calkins, in his book They Broke the Prairie, wrote that Gale was a cool dude in social relations, but, “narrow and intolerant in religion,”. He, along with the other founders, expected the people to spend their time “in work or worship” (p. 327). The article The Origins of Knox College on the college’s website emphasizes that the manual labor form of education, built upon the self-reliance and “health and bodily vigor” that was sometimes lost when students were dedicated exclusively to studies to the neglect of physical exercise. However, I think it is odd, and a little ironic, that in an abolitionist college low-income students had to perform arduous work for—technically—no salary.

It is important, however, to recognize that the idea of a manual labor college, especially an abolitionist one, was highly innovative and advanced for the time. Speaking about abolitionism, everything you heard about Knox College and Galesburg being anti-slavery advocates is very much true. The purchased prairie grassland quickly became the main center of the underground railroad in Illinois. For that reason, the number of Black people coming to town started to increase a lot in the 1830s. The early Black citizens of Galesburg played a variety of roles in town. Black people were farmers and establishment owners and had political power. After some years, however, the scenery completely shifted.

Segregation in Marriage

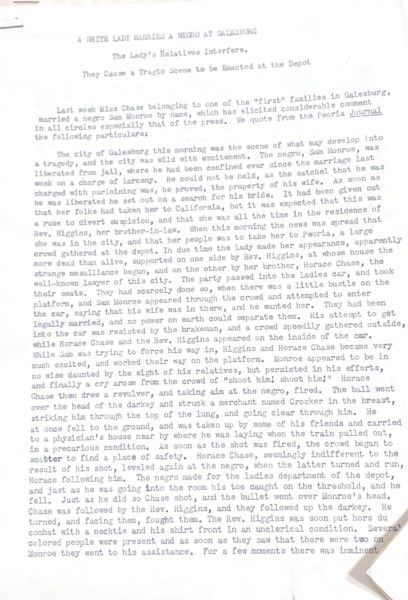

“A white lady marries a negro in Galesburg”, Schuyler Citizen, Rushville, Illinois, September 23, 1880.

Not even fifty years after the establishment of The Knox Manual Labor College, marriage was deemed socially not okay between a white woman and a Black man in Galesburg. Meanwhile, shooting a Black man in public seemed perfectly fine to many of the residents. “A White Lady Marries A Negro At Galesburg,” is a newspaper article published by Schuyler Citizen in September 23, 1880, that reports the incident in which a Black man was almost shot trying to get to his white wife. Miss Chase was a lady from a rich family in Galesburg who married a Black man named Sam Monroe. This caused a stir in town. According to the newspaper, to “preserve the honor of the family’s name,” her family organized a plan to move her to Peoria.

On the day of the move, Monroe was released from jail. He had been held on a larceny charge, but he proved that the item he was accused of stealing belonged to his wife. Meanwhile, Miss Chase appeared at the train station looking, according to the newspaper, “more dead than alive,” while being supported on one side by Rev Higgins and on the other by her brother, Horace Chase. The newspaper does not explain the reason for Miss Chase’s poor appearance. Perhaps she was sick or under the influence of a substance.

The family had just gotten in the car when Sam Monroe appeared at the door, requesting to get to his wife. His attempt to get in the car was resisted by the brakemen, and a crowd quickly gathered as Higgins and Horace Chase tried to make Monroe stay back. Finally, a cry crossed the crowd saying “Shoot him! Shoot him!”. Horace Chase then drew a revolver and, aiming at Monroe, fired. The bullet went over Monroe’s head and struck a merchant named Croker in the ribs. Monroe, under gunpoint, was chased away from the depot by Horace.

Segregation in Employment

By the beginning of the 20th century, the job variety that initially existed for Black residents had disappeared. In the essay, ‘Negro Youth In A Small Midwestern City,’ written during the 1930s, Knox Professor J. Howell Atwood noted that Black people often had jobs as employees but rarely as owners. Their work situations were pretty unstable, mostly part-time or low-paying. Atwood reported that Black people faced limited job opportunities, with many working in domestic service, janitorial roles, and manual labor. There was a clear hierarchy when it came to employment, with positions in places like the post office and banks mostly held by white people. Only a small percentage of Black residents had skilled jobs, and many relied on relief programs for survival.

A live example of Galesburg’s employment racial segregation is the essay, “The Tie Plant Colony at Galesburg, Illinois,” by G. Grace Wargo. The C.B. and Q. Timber Preservation Plant started in 1908, as a project to increase the life of timber. Wargo interviewed Mr. Duncan, manager of the plant since 1927, who said: “We employ negroes exclusively to carry ties because it is a very difficult task. Only men of superb physical condition can stand the work. The northern negro lasts on the average of a half a day at the job. While colored men from Ohio, Mississippi, Missouri, and other southwestern states have a strong physique, he is also trained from early childhood to carry heavy loads,”. Excuse me, Mr. Duncan? You not only shamelessly admit that you have been hiring exclusively Black people to do all the heavy work in the company, but also justify it by using highly stereotyped concepts about Black men. What happened to the creation of the town, when we were all equal?

Segregation in Residential Areas

Segregation did not extend just to jobs, but also to people’s homes. In the 1930s, most Black families in Galesburg were crammed into the southwest part of the city, close to industrial areas. Even though they owned homes at about the same rate as others, their houses were much older and often lacked things like running water and indoor toilets. Many were deemed unfit to live in.

At the C.B. and Q. Timber Preservation Plant, half the workers were white and half were Black, but the Black workers lived in a little settlement made up of old red boxcars right on the railroad grounds. G. Grace Wargo described the Tie Plant Colony as a long row of these boxcars, with a church at one end. The place had no gas or electricity, so the residents used fire for light and heat. On top of that, the people who lived in the Tie were seen in a derogatory manner by those who did not live there. Before she visited, people warned Wargo that the colony was dangerous and that the folks living there were “wild,”.

“No one seemed to know much about the colored colony at this plant, but everyone was sure it had a bad reputation,” Wargo noted.

The Lake Storey Incident

The Lake Storey segregation issue arose in 1930 when the city was opening a large park and bathing beach. A Black man and some white young men got into a fight, and for fear of more incidents, the city authorities separated Lake Story into the north (for white people) and the south (for Black people).

Alva Early, a student at Galesburg High School in 1959, was denied his diploma after he and some friends had a picnic on the north side of Lake Storey Park, which was reserved for white people. The school was aware of the segregation between white people and Black people and agreed with it. By taking away Early’s diploma, it was as if the school authorities were saying, “You do not believe that your race is inferior, so we are going to punish you,”.

More and more Racial Stereotypes…

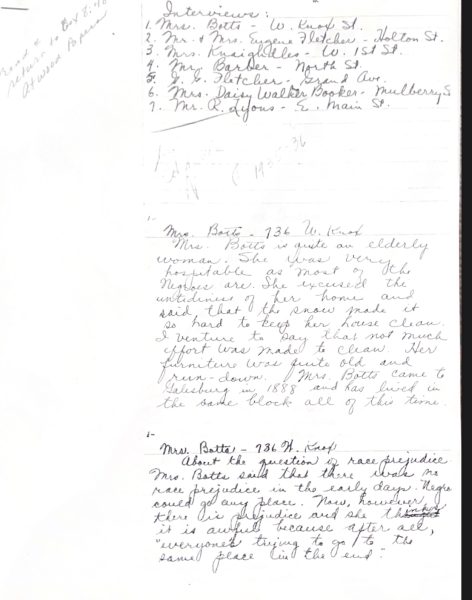

- Howell Atwood interviews with Black people in Galesburg in the 30s, J. Howell Atwood Archives, Box 9.

The document Six Weeks Report for Sociology M. Holmes narrates Holmes’ views about the church of the White Horse religious group located blocks away southwest of Knox College. The congregation was exclusively composed of Black people (Guess what? Religious life was also deeply segregated in Galesburg).

Holmes described the congregation this way: “These Negroes, while singing, seem to forget their best Sunday suits and their shiny rayon stockings; they become true natives, and sway slightly from side to side in rhythm with the hymns,”. He went on to say, “Certainly these people were thorough Christians, yet they sounded more Pagan than any group of natives would on a movie set,”. (J. Atwood; M. Holmes, 1930s).

- Holmes uses the term “native” in a negative way, implying that when the congregation sang, they set aside their, “suits and stockings”—essentially, their ties to “civilization”—and became “wild.” He also suggests that by embracing this so-called “native” quality, Black residents are somehow “Pagan.” Like that, M. Holmes manages to be offensive to two groups at the same time, painting Black people and Native Americans as less “civilized” and, by extension, less “advanced” than white people.

Atwood did a lot of research regarding racial issues, but, as a white man, he was not free of building stereotypes from a group that he was not part of. Atwood’s biased views seem to be unconscious, and like in Homes’ case, seeping through in his writing.

During Atwood’s interviews with Black citizens in Galesburg, he found most of them welcoming, which led him to mistakenly link Blackness with good hospitality. However, when he visited Mr. and Mrs. Eugene Fletcher on Holton Street, he was surprised to feel unwelcome.

“Mr. Fletcher did not seem to be particularly interested in talking to me. He was, I believe, the only Negro who did not ask me to come in and sit down,” noted Atwood, “Mr. Fletcher is the Negro undertaker. He didn’t seem to have the friendly, cordial feeling that undertakers should have. Perhaps he resented my color. I hope I didn’t misjudge him.”

Conclusion: Anti-Slavery? Yes! Anti-Racist? Well…

Knox College emphasizes its abolitionist origins on its official website but says little about Galesburg’s historical prejudice against Black people. This omission creates a lack of awareness about the deep-rooted discrimination in the town, despite its foundation on abolitionist ideals.

I believe one way to solve this issue is by sharing more about the discrimination that’s been around from the late 19th century to now, like segregation in jobs, housing, and places like Lake Storey. It’d also be helpful to point people to resources where they can learn more about the topic. The books I found in the Seymour Library Main Stacks had plenty of information about the town’s foundation, culture, agriculture, and social life in its early days, but nothing was mentioned about the prejudice Black people suffered during that time.

They Broke the Prairie, published in 1937, does not address segregation and racial prejudice, which were already apparent by that time. The author, Calkins, portrays a picture of runaway slaves living happily in Galesburg, mostly from a white perspective, making it hard to understand what life was actually like for Black residents back then.

I appreciate the resources at Seymour’s Archives, and I wish more people could see what I found there. Atwood’s papers were crucial for my research, since, without them, I am afraid I would not be able to come in contact with most topics relevant to this article. Considering all the cases and reports I found, it is possible to conclude that Galesburg was indeed anti-slavery, but not anti-racist. As much as Knox College has the right to remember its crucial role in abolitionism and the Underground Railroads, the struggles faced by racial minorities in Galesburg must also never be forgotten.

Eleanor Lindenmayer • Oct 14, 2024 at 2:23 am

I always enjoy your distinctive voice!

Julia Maron • Oct 14, 2024 at 3:01 pm