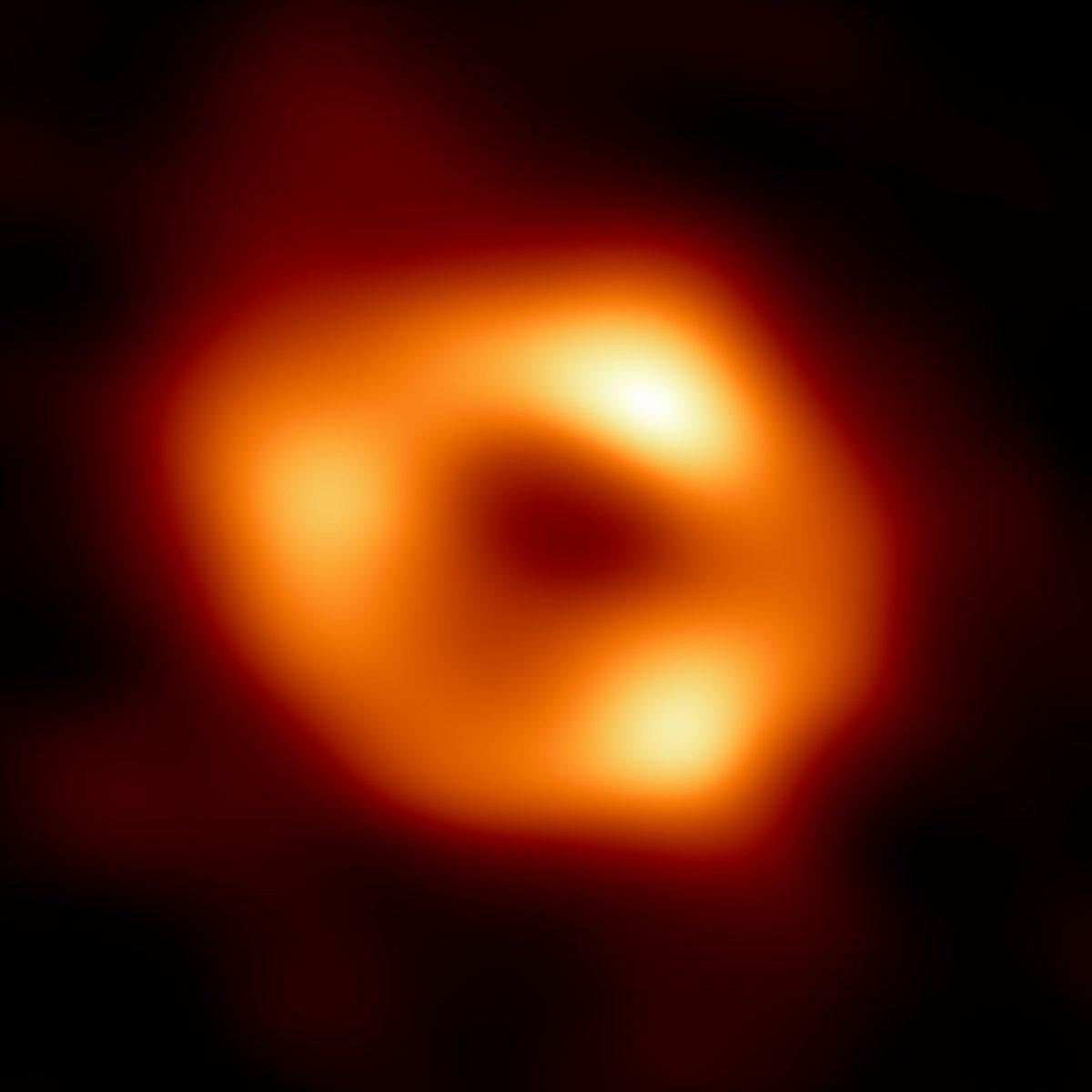

On May 12th, 2022 in an around-the-world-simultaneous press conference, scientists released the first picture of the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy, Sgr A* (Sagittarius A star).

Astronomers have long known about the small dense object in the center of our galaxy – dubbed Sgr A* for its location in the constellation Sagittarius. A mess of stars orbit tightly around Sgr A*, some with orbits as small as the distance between the Earth and the Sun. This may not sound so impressive, but it has been observed that Sgr A* has a mass 4 million times that of the Sun, and yet is barely larger than the Sun in terms of radius.

An object of this mass and such little size could be nothing except a supermassive black hole, but scientists declare nothing true without evidence. This photo is finally that evidence.

Sgr A* is the second black hole photographed by the scientists of the Event Horizon Telescope. The first was M87*, a black hole 55 million light years from Earth nestled in the center of the Messier 87 galaxy. While Sgr A* is massive, it has nothing on M87* which is 6.5 billion times as massive as the Sun.

What is a black hole?

Black holes are what is left after the explosive death of a supermassive star. It is an object so massive that even light and time cannot escape its gravity. Like any massive object in space, other bodies can orbit safely, like those aforementioned stars.

When objects or gas are close enough, they are slowly whirlpooled in, causing the glowing accretion ring that surrounds the black hole. Once they pass the horizon, even light cannot escape.

But the supermassive black holes at the center of the Milky Way and Messier 87 are much too large to be the remnants of a once massive star and must have been formed in some other way. Modern theories assume that there are supermassive black holes at the center of all galaxies, and they are involved in their formation.

How was it photographed?

The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) – named for the event horizon in a black hole – is the largest telescope ever built. It’s actually not one telescope – it’s 8. The EHT is 8 radio telescopes all around the world linked together to create one ‘earth sized’ telescope. It was designed specifically for the photographing of black holes and has an unprecedented sensitivity and resolution.

“Over 10 years ago, we linked radio dishes in California and Arizona to the SMA and other telescopes in Hawaii, allowing us to discover features in Sgr A* that were the size of the black hole shadow. This breakthrough launched the EHT, leading us to the wonderful Sgr A* image revealed today,” said Sheperd Doeleman, founding director of the EHT.

The telescopes observed in tandem during several nights in 2017, collecting a mountain of data. They photographed both M87* and Sgr A* during this time.

The photo of M87* was released on April 10, 2019. It was much easier to put together the photo of M87* as it is so much larger than Sgr A*. All the photos taken of M87* looked about the same.

The photos of Sgr A* did not. It takes almost a day to orbit M87*, while it only takes minutes to orbit Srg A*. This means the brightness of Sgr A* was constantly changing, making it much more difficult to capture.

“Sgr A* was changing rapidly as the EHT Collaboration was observing it – a bit like trying to take a clear picture of a puppy quickly chasing it’s tail,” EHT scientist Chi-kwan Chan, from Steward Observatory and Department of Astronomy and the Data Science Institute of the University of Arizona, US said.

The final image is an amalgamation of thousands of images. The scientists also clustered similar images into 4 more photos with slightly different features.

These photos were the work of over 300 researchers at 80 institutions.

Why is this important?

Science is all about matching hypotheses to observed evidence, something that is particularly difficult in astronomy. Black holes have long been predicted in Einstein’s theory of General Relativity, but until the photo of M87* in 2019 there was no undeniable, observable evidence.

The scientists are particularly excited to now have two vastly different black holes to compare and contrast.

“We have two completely different types of galaxies and two very different black hole masses, but close to the edge of these black holes they look amazingly similar,” Sera Markoff, Co-Chair of the EHT Science Council and a professor of theoretical astrophysics as the University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands said. “This tells us that General Relativity governs these objects up close and any differences we see further away must be due to differences in the material that surrounds the black holes.”

They are also using the data to test scientific theories and models of how gas behaves around black holes, as the gravity is not fully understood

“We can go a lot further in testing how gravity behaves in these extreme environments than ever before,” Keiichi Asada, and EHT scientist from the Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Academia Sinica, Taipei said.

What’s next?

The EHT has already been run again in March of 2022, with even more telescopes added to the system. They hope to share more impressive images and short videos of black holes in the near future.

“Never before have we had so much data on a black hole, and it comes at a crucial moment when our models of how gas behaves in its vicinity are in dire need of revision,” Center for Astrophysics – Harvard and Smithsonian astrophysicist Angelo Ricarte said. “The EHT is ushering in a new era of precision black hole astrophysics.”